Devolved and local elections 2016: make what you will

Early May saw an array of different elections across the UK, and although I initially had no intention to write about them the results were actually quite interesting. There's not a clear pattern across the UK of success or failure for any of the political parties, so a lot of fine detail to examine. This isn't to say that these elections haven't been good or bad news for any of the players involved, some parties clearly had better nights than others, but depending on what elections you focus on and how you judge success you can always find a silver lining to cheer you, or see a dark cloud hiding behind glittering political achievements. Hence the title: make what you will.

Northern Ireland

I thought it best to tackle Northern Ireland first as its party system is almost completely distinct from that of the rest of the UK and I thought it would interrupt the flow to start talking about this other party system mid-way through talking about the Great British parties. As far as I'm aware there were no projections made of expected results for this election and therefore nothing to under- or overperform against, though there were polls, and success can therefore be largely measured against previous NI Assembly and Westminister results.

The Northern Irish Assembly at Stormont. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

How it works

First, a quick overview of how the NI Assembly works and how it selects its members of the local assembly (MLAs):

The Northern Irish assembly works on a power sharing basis with typically the vast majority of MLAs being part of the government. Every MLA also designates themselves unionist, nationalist or other (this designation can be changed at any time but only once per term). Within the government ministerial posts are allocated between parties by the D'Hondt system (explained in the Scotland section) to determine how many ministers each party is due. The three exceptions to this allocation are for the First Minister and Deputy First Minister (who are the leaders of the largest unionist and nationalist parties) and the Minister of Justice who is elected in a cross-community vote and has so far always been from the non-sectarian Alliance Party.

Certain votes require cross community support and therefore have additional requirements such as minimum requirement of MLAs from each sectarian bloc supporting the motion. Some of these are "hard wired", electing the speaker for instance, but any motion can be subjected to this more stringent vote if enough MLAs raise a petition of concern. The intention is to prevent legislation that could damage any community in NI, but it has also been abused in the past - such as being used by the DUP to prevent gay marriage from being legalised in Northern Ireland, despite it (narrowly) having a majority in favour of it in the Assembly and it clearly not affecting the unionist community any more than the nationalists.

The powers of the Assembly are defined by exclusion, anything not explicitly excluded is considered part of the Assembly's competency. These excluded areas can be reserved (powers may be granted to the Assembly at a later date) or excepted (to be retained by Westminster indefinitely). Examples of reserved powers include postal services, intellectual property law, telecommunications and consumer safety; and examples of excluded powers include defence, foreign affairs, elections, currency and nuclear energy. Powers, notably justice and policing, have been transferred to the Assembly since its inception.

The electoral system used is the single transferrable vote (STV), with 18 constituencies electing 6 MLAs each. The intention of this is to maximise representation of voters who may be in the minority in an area, and in this I believe it succeeds. I would go so far to say it's actually the best implemented voting system in the devolved legislatures.

STV works by electing multiple representatives per constituency, with voters ranking their favoured candidates by preference (up to the point where the voter no longer cares). After voting a quota that candidates must reach to be elected is established. Typically the proportion of the vote needed to meet the quota is one divided by the number of seats available (plus one), plus one vote. So, if there are six seats available each candidate needs 1/7th of the vote, plus one more vote (about 14.3%). Not too complicated.

Vote counting begins, starting with first preference votes and any candidates who have met their quota are elected, if all seats are filled the vote ends. If not, then any votes received over the quota for elected candidates are redistributed to the voters' second preference candidate. Should all the seats still not be filled then any votes over the quota for a candidate elected on the second count are transferred to the voters' third preference candidate and the process repeats indefinitely.

If not all seats are filled and transferring excess votes cannot fill any more quotas then the candidate with the lowest vote is eliminated and their votes redistributed to their voters' second preference vote. Sometimes many rounds of counting are run to fill the last few seats, one candidate in the 2016 elections was elected on tenth preferences!

This is actually a slightly simplified description, in practice it's done slightly differently so that the order of vote counting cannot affect the end result, but in any case the broad jist of STV is that you have one vote but it moves if it would be "wasted". The system is, in fact, specifically designed to minimise wasted votes.

STV, implemented well, tends to be approximately proportional to first preference votes. By design a deviation from this proportionality exists - getting second and third preference votes can be vital for winning seats so a party which is seen as extreme, or which has become particularly unpopular for other reasons, might get less votes transferred to them and therefore underperform relative to their vote share.

Other sources of disproportionality can include a party running too many or too few candidates in a constituency, a party being punished for having support concentrated across a boundary (a problem with any system with constituencies) or a party missing a quota by a small amount and getting punished excessively for it (a problem with any system). I would imagine the last two of these would be pretty minor effects under STV with six-member constituencies though, and the first is arguably more the fault of the party running candidates than the system itself.

Parties

Represented in the 2011 Assembly there were five parties seen as being major and established: the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), Sinn Féin (SF), the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and the Alliance Party. The first two are unionist parties, favouring remaining in the UK, and are right wing - with the UUP tending to be the more moderate of the two. SF and the SDLP are both nationalist and left wing, though they sometimes take more socially conservative stances when the left wing stance would be contrary to Catholic sensibilities. SF is more stridently nationalist, with the SDLP viewing unification as more of a long-term goal. Alliance is a (broadly) left wing/liberal non-sectarian party, that grew from a moderate unionist group. There is also the non-sectarian Green Party in Northern Ireland (a branch of the Irish Greens), Traditional Unionist Voice (a hardline unionist party that opposes the Good Friday agreement) and an independent unionist. Unrepresented parties worth mentioning include the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP), a fringe left-wing unionist group that has been represented in previous Assemblies, and the People Before Profit Alliance (PBPA), a pan-Irish hard left party that has recently gained representation on Belfast Council and has no known stance on the sectarian issue (designated as "other"). Many, but not all, sectarian parties have alleged historical links with paramilitary groups.

UK parties tend not to run in NI elections but there are exceptions. UKIP and the Conservatives run candidates in Northern Ireland (the BNP used to as well) but have almost no electoral success. Labour and the Liberal Democrats prefer to maintain close ties to their sister parties, the SDLP and Alliance, instead - these parties can take their whip in Westminster. Although the Conservatives run their own candidates at the moment they have historically had close ties with the UUP, with the UUP historically taking the Tory whip in the Commons and the two parties running joint candidates as recently as 2010.

Regarding parties from the Republic of Ireland there had been talk of Fianna Fáil fielding candidates but that never materialised. The Green Party in Northern Ireland is also a branch of the Irish Green Party while Sinn Féin, of course, also operates both sides of the border, as does the PBPA.

The results

Northern Ireland Assembly Results 2016 (First Preference Vote %)

Northern Ireland Assembly Results 2016 (Seats)

Broadly the order of the day was stasis. All of the five "established" parties lost vote share but only very modestly. Sinn Féin lost one seat and 2.9% of the vote, the SDLP lost two seats and 2.2% of the vote and the rest stayed pretty steady and lost less than 1% of their vote.

The parties that gained from SF's and the SDLP's losses were the Greens in Northern Ireland and the People Before Profit Alliance (the second of which entered the Assembly for the first time) representing a slight shift away from nationalism. These were also the only two parties to increase their share of the first preference vote by over 1%, though other minor parties and independents all had small vote share increases.

As I had said, there were no projections to compare performance so in a sense no-one really over- or underperformed versus expectations. There were polls however and they were broadly accurate (though understating the DUP and overstating the UUP by a few percent). The slight shift from nationalist parties to the Green and PBPA might reflect a younger electorate starting to reject sectarianism but it's difficult to make a comment on a trend like that on the basis of one election result, so it may be nothing so significant.

We can safely say that the PBPA did well from this election and that the SDLP, continuing its long term decline, did not. The UUP had expected to make gains, as they did in the general election, but these did not materialise so perhaps it could be said that they also had a bad election.

Post-election most things have gone fairly smoothly, save for the UUP deciding to be in opposition - which they had done in the previous session as well. So this was hardly a bolt from the blue.

Scotland

How it works

The Scottish Parliament works far more conventionally than the Northern Irish Assembly, with a government and an opposition. The parties of note are also the familiar UK parties, plus the SNP, though it may be worth mentioning the hard left alliance RISE - Scotland's Left Alliance, which includes the Scottish Socialist Party which has gained seats in the Parliament in the past.

The Scottish Parliament, like the NI Assembly, has competency in all powers not specifically excluded or reserved by Westminister, and its list of competencies is longer than the other devolved legislatures. Beyond the powers previously mentioned that Northern Ireland has the Scottish Parliament also has some additional areas of competence such as limited taxation and borrowing powers, It also has the power to legislate on Scots law, a legal system distinct from that applied in the rest of the UK that long pre-dates devolution.

The electoral system used is the additional member system (AMS), more specifically the mixed member proportional (MMP) system (majoritarian variants on AMS exist). In this system there are members of the Scottish parliament (MSPs) representing 73 first-past-the-post (FPTP) constituencies and 56 members elected from a (D'Hondt) party list - constituency MSPs and list MSPs respectively. The list is utilised to compensate for disproportionality in the FPTP result - the list MSPs are intended to make the overall result proportional (the details will be explained a bit later if you're interested). However, unusually for an MMP system, Scotland has 8 seperate list regions electing 7 MSPs each rather than one 56 member list. Germany and New Zealand, who use MMP for their national parliaments, use a single national list and this is very much seen as part of the standard implementation ofMMP. Each voter has two votes, one for the constituency and one for the list, these can be for the same or different parties.

The FPTP constituencies are elected exactly as you would expect, as in Westminister. The list constituencies use closed D'Hondt party lists. This means that the order of candidates elected is chosen by the party with no direct input from the voters and the seats are allocated proportionally to parties - so if party X gets enough votes for three seats then numbers one to three on their (pre-existing) list of candidates are elected, and the voters have no mechanism to change what candidate is on what position on the list. D'Hondt refers to the method used for calculating the proportional allocation of seats. If you aren't interested in the nitty gritty then the long story short is that D'Hondt marginally favours larger parties compared to other methods of calculation. The next two paragraphs contain quite fine detail on how the calculation works so if you aren't interested then please skip them.

The difficulty in proportionally allocating seats is how to get an integer (the number of seats won) from a non-integer (the true proportion of the vote won). Common ways of proportionally allocating seats can be divided into largest remainder methods, which use quotas like in STV, and highest averages methods where a series of quotients are generated for each party running. D'Hondt is one of the latter methods. Quotients are generated for each party by dividing the number of votes they won by every number from 1 to the number of seats available, and the seats are allocated by picking the highest value quotients amongst all parties until all seats are filled, this results in seats being allocated proportionally. A visual representation of D'Hondt follows. Another common method of calculation is the Sainte-Laguë method where the votes are divided by every odd number up to the number of seats available, this slightly favours smaller parties.

An illustration of how seats are calculated from party lists for a hypothetical seven seat constituency - first panel is D'Hondt system and second is Saint-Laguë.

With the illustration you can see how the quotients are generated from each party's vote and how the top seven quotients are picked from all quotients generated. I've included both D'Hondt and Saint-Laguë methods to demonstrate how the latter favours smaller parties, but also to show that neither is inherently "fairer" - party C is denied a seat it is proportionally "due" under D'Hondt and party A is denied a seat it is "due" under Saint-Laguë.

In MMP systems if a party wins a seat in the constituency vote then they are ineligble for the first seat they would have otherwise won on the list vote. This allows the compensatory aspect to come in. In Scotland there is also no explicit threshold of the vote that a party must gain in order to be eligible to win seats from the lists, as is quite common internationally - typically these thresholds are quite low, between 2-5%, but some countries using party lists (like Turkey) set very high thresholds (10% in that case).

However simply due to the rules of mathematics there is still a minimum threshold of the vote you need to win your first seat in practice. Under D'Hondt this is effectively 1 divided by the number of seats available, plus 1 - assuming there are more seats available than parties running. So a three seat list requires 25% of the vote to gain a seat, a four seat list requires 20%, five about 16%, six about 14% et cetera. Under MMP, as the parties winning constituency seats are ineligble for a number of list seats equal to the number of constituency seats they have, this effect is reduced substantially - in 2016 the lowest percentage of the vote that resulted in a seat won was 5.3% (for the Greens), when the effective threshold without the compensatory mechanism would have been 12.5%. So in practice this is not such a big effect in Scotland but it may be a source of disproportionality in Welsh Assembly elections, which use the same system with much smaller lists. The fact that there are fewer list MSPs than constituency MSPs in the first place also provides a limit on how much compensation the list MSPs can provide, and therefore is a potential source of disproportionality in theory. Again, I'm unsure if this has ever affected a result in practice in Scotland but it is more conceivable in Wales.

Finally a complication of MMP is what to do with overhang seats, where a party wins more constituency seats than it would be from the list vote. There are four ways to deal with this: disallow the party any constituency seats it won past its proportional share, allow the overhang seat and increase the size of the legislature by one, allow the overhang seat but also add enough list seats to restore proportionality (increasing the size of the legislature), or maintain the size of the legislature by reducing the number of available list seats for other parties by one (reinforcing the disproportionality of the overhang). New Zealand uses the second option (allowing some disproportionality), Germany has recently adopted the third (seeking to minimise disproportionality) and sadly Scotland uses the fourth option (reinforcing disporportionality to maintain a constant size of legislature). London and Wales also do this, I believe, but I found it hard to find concrete information on this topic for those bodies.

Dealing with Overhangs in MMP

Broadly speaking Scotland's MMP system actually quite well implemented in practice but given the system is supposed to be proportional the choice to adopt regional lists and the current overhang rules seem like very strange choices.

The Scottish Parliament. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

The results

Scottish Parliament Election 2016 (List Vote)

Scottish Parliament Elections 2016 (Seats)

Scottish Parliament Election 2016 (Constituency Seats Only)

As a forewarning for this election (and for Wales) I've made the assumption that a swing to a party in Holyrood translates into a swing in Westminster in the same area. This might not be true (a lot can happen in four years, people may just vote differently etc) so feel free to take any views hinging on this assumption with a pinch of salt.

Broadly I would say that from these results there are positives and negatives for all parties save for Labour and the Conservatives. There doesn't seem to be any clear bright side to Labour's results and there's no obvious hitch in the Conservatives' success in Scotland.

Labour lost 7% of their list vote, taking them below 20%, and lost the vast majority of their constituency seats (particularly in the centre of Scotland) - they are now behind the Conservatives in overall seats and behind both the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats in constituency seats. The sole mitigating factor for them is the gain of Edinburgh Southern from the SNP which may bode well for their their retaining the equivalent seat in the House of Commons come 2020 - though the likelihood of boundary changes make that less certain. Otherwise a catastrophe for Scottish Labour which would have been unthinkable only a couple of electoral cycles ago.

Meanwhile the Conservatives enjoyed a seemingly unlikely and substantial boost under the banner of their fairly moderate leader Ruth Davidson (Tories south of the border, take note) with a jump of 10% of the vote and the gain of 4 consituency seats, including one for their leader (Edinburgh Central). They also beat the polls. This proved enough to take them into a clear second place in vote share, constituencies won and overall seats won. I'm unsure of the cause of this meteoric rise - a rehabilitation of a fairly battered brand? A new and popular leader? The Conservatives becoming a general receptacle for unionist votes? But no matter what caused their spike in popularity they've little to worry about for now. If I'm to find a little dark lining to accompany their silver cloud it would be that the Scottish Parliament constituencies they gained don't look likely to me to translate into Westminster seats judging by the how far away the Conservatives were from winning these seats in 2015 (big swings in Holyrood but it doesn't look like enough), but otherwise all sunshine in the blue corner.

For the SNP they have a set of results that most political parties would kill to attain. They remain unquestioningly dominant in Scottish politics and, although their list vote dropped a notch, their constituency vote even advanced a little, and from a very high base. From this I think we can conclude that the Holyrood result doesn't suggest any SNP Westminster losses in 2020 are particularly likely except where the SNP lead in Westminster is reasonably narrow and where a challenger party gained a large increase in the vote in this Holyrood vote. I could only find two constituencies that fit that bill, though there's the possibility I missed some.

However, the big SNP story is that they failed to retain their majority in the Scottish Parliament. This probably shouldn't be a surprise as they strictly speaking shouldn't have attained one last time in a proportional system, but it does seem to have flustered the SNP perhaps more than it should. The polling also predicted they'd stay steady in vote share rather than losing a few votes as they did, so perhaps this also unnerved them. A disappointment by their standards but nevertheless still an excellent result for the SNP.

For the Scottish Liberal Democrats you could argue that they had a sneakily good night, despite no net gains and slipping to fifth place. Their voteshare actually barely moved, but on the constituency vote they experienced a very advantageous shift in where their votes were concentrated. Their vote was reinforced substantially in some former strongholds in the mainland Highlands and in their Orkney seat, which is now a safe seat after being marginal in 2011. They also gained two constituencies (from the SNP) - Edinburgh Western and North East Fife, both former areas of strength in Holyrood and Westminster. If the boundary review is kind to them these results may be a good omen for maintaining Orkney & Shetland and possibly gaining North East Fife in 2020.

The downsides of their night are fairly obvious - slipping to fifth (behind the Greens) and their nearly total static vote share, a good night for setting up for 2020 but not so much on its own terms. This means that the gains they made are offset by losses in less fertile areas (including areas which pre-coalition were very achievable target seats), which is all very well for this election but at some point recovery has to mean actually getting more votes.

Finally for the Scottish Greens - a good night. A bump up in the vote and a tripling of their seat count (to 6) and gaining fourth place in the Parliament aren't to be sniffed at. This all happened on the list vote so there's not really much geography to discuss save that they did strongest in Lothian and Glasgow, and weakest in West Scotland (where they won 5.3% of the vote, the lowest winning percentage of the night) and Central Scotland (where they won nothing at all). They also won no MSPs in South Scotland but they ran no list candidates there. The downside to their result is probably just that the strength of their increase in seats is not reflected by their fairly modest jump in the vote - it seems like they probably got less than their proportional due last time around, magnifying the effect of their boost in popularity. Furthermore, some polls suggested they'd get a higher share of the vote than they did, but I think they're probably still happy with this result.

Finally for the parties that were not in the previous parliament there's little obvious to celebrate in these results. UKIP remains a fringe party in Scotland, at least outside European elections, and the SSP is evidently remaining dead for the time being.

After the election some minor post-election drama has come from Alex Salmond. He has got upset at the system for reportedly denying the SNP a second majority and has advocated a switch to a pure party list system using one national list. I suspect this means he hasn't thought this through very well, as the SNP were on around 45% of the list vote in 2011 and around 41% this time on the list vote. Given the parliament has 129 seats this means that in 2011 the SNP would have probably not have even had a majority under a list system and would not be within touching distance of one now - the minor disproportionality of the system actually favours the SNP at the moment. A strange outburst, but I suppose some credit must be given for not suggesting a completely self-serving change in voting system (to FPTP for instance).

Wales

How it works

The National Assembly for Wales operates using an MMP system near identical to that of Scotland, save that only 20 of its 60 AMs are elected from party lists and that each regional party list has only four positions. This results in a far less proportional system than the other devolved legislatures, although it is often called proportional in the media this is a bit of a misnomer.

The powers of the Assembly are also much more limited than those of Scotland or Northern Ireland but have grown substantially since its founding. It currently has the ability to directly pass primary legislation, whereas it originally could only pass secondary legislation (until 2006) and needed to have all votes confirmed by Westminster (until 2011). Unlike Scotland and Northern Ireland its devolved powers are explicitly stated rather than implied by exclusion, it has twenty areas of competence that are explicitly defined (such as health, education, housing, transport and the Welsh language). Everything else is handled by Westminster.

The Welsh Assembly (Senedd) and Cardiff Bay. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

The results

Welsh Assembly Elections 2016 (List Vote)

Welsh Assembly Elections 2016 (Seats)

Welsh Assembly Election 2016 (Constituency Seats Only)

So I'm sure by quickly looking at the graphs that you can see that despite being a nominally proportional system that the Welsh Assembly results are actually very disproportional this year. Honestly I find it hard to say that there are any real winners from this election and every picture is mixed.

Labour had what looks like, by seat count, a decent night - only down by a single seat (Rhondda). However, this masks an over 5% drop in voteshare in the list vote and an over 7% drop in voteshare of the constituency vote. A mixture of luck in the constituencies and a wonky voting system buffered them from losing a fairly substantial number of seats, so while they had hoped to gain seats to win a majority they were actually extremely lucky to even retain the position they had. So, to put it mildly, although they lost only the 1 AM and therefore are in a very strong (but not unassailable) position to form the next Welsh government the result is deceptive and looks better than it is. While not disastrous these results don't bode well for 2020 in Wales or indeed for the next round of Assembly elections.

With the Conservatives there's not too much to say beyond that their performance was a bit weak. Their list vote was down by well over 3% and they lost a few (list) seats to Plaid Cymru and UKIP. The positive side of things for the Conservatives are that their drop in support was not very large and that the huge drops in Labour constituency votes have made some Welsh Assembly constituencies that had been safe for Labour into Labour-Conservative maginals. The Welsh Conservatives failed to move forward, they even moved a bit back, but they're in a good position to gain some seats if Labour's misfortunes continue.

Plaid Cymru had a small swing in the list vote to them and an even smaller one in the constituency vote. I would imagine that the latter may be almost solely due to their big success of the night, the taking of the (apparently not so) safe Rhondda seat from Labour on a massive swing. Impressive as that is, and it definitely is impressive, their position seems pretty static overall to me - at best a small advance. I can't see the seizing of Rhondda in the Assembly translating into a 2020 Plaid Cymru gain as Leanne Wood (the new AM for Rhondda and Plaid Cymru leader) has a strong personal vote, which the prospective parliamentary candidate for the Westminster seat may not have. Beyond this Chris Bryant (the Labour MP for the Westminster seat of Rhondda) also has a strong personal vote that any Plaid Cymru challenger would have to overturn. Plaid had also been polled to perform better than they actually did on the day, so this election may perhaps be a disappointment to them.

UKIP broadly had a good night, entering the Welsh Assembly for the first time and in pretty decent numbers though with some fairly controversial names on their party list. Geographically there's little to say except that they were slightly stronger than normal in South Wales East, and slightly weaker in South Wales Central. Otherwise quite uniform. There may, however, be a tinge of disappointment for the purples as they had been polled to perform a fair few percent better than they did and were reportedly expecting more AMs. It will be of great surprise to anyone to who follows UKIP that post-election they almost immediately got to infighting, which is quite uncharacteristic of their behaviour...

The big losers of the night were the Liberal Democrats. The yellows, to be frank, had a fairly limp performance in Wales. Aside from a massive swing to Kirsty Williams in Brecon and Radnorshire (boding well for retaking the seat in 2020?) there is really no good news. There was no progress in any potential target seats, even Cardiff Central (formerly held in both the Assembly and in Parliament) which was a widely expected gain saw a small drop in their vote. In seats like Monmouthshire and Ceredigion that should be viable targets they remain very distant challengers (though still second) and their list vote dropped marginally.

However they did have a disastrous night of what was just a mediocre performance - losing 4 AMs for less than 2% of a loss in list voteshare. Given Labour lost over 5% (and lost 1 AM) and the Conservatives lost over 3% (and lost 3 AMs) this is actually quite a perverse outcome for a nominally proportional system. Though, to play Devil's Advocate this was, in a way, deferred punishment from 2011 (where they lost almost 4% of the vote but only 1 AM). Personally though I don't think two perverse outcomes balance each other out, even if one punishes and one rewards the same party in successive elections.

Finally, the Greens once again failed to make it into the Welsh Assembly, which proportionally they should have done (just). I doubt this surprised them or anyone else.

Essentially the picture is of near stasis for Labour and Plaid Cymru in seats with a minor decline for the Conservatives, a breakthrough for UKIP and disaster for the Liberal Democrats. But this picture hides a lot of detail as the voting system distorts the results an awful lot: the picture is quite a lot worse for Labour and quite a lot less bad for the Liberal Democrats than it seems - though it's not a disaster for Labour and not a good result for the Lib Dems either.

To be honest I find the Welsh Assembly system to be quite random with its results, with the consistency vote favouring Labour, delivering near majoritarian results from a proportional system. The system is quite capricious in most other respects - for instance Plaid Cymru won 21% of the list vote and 15 seats in 2007 and 20.8% of the list vote but only 12 seats in 2016.

The leaders of the four parties represented in the 2011 Welsh Assembly, before the 2016 election. Carywn Jones (Labour), Leanne Wood (Plaid Cymru), Andrew R. T. Davies (Conservatives) and Kirsty Williams (Liberal Democrats).

Post-election some big drama has ensued. Leanne Wood put herself forward against incumbent First Minister Carwyn Jones - and tied with him for votes due to the support of Conservative and UKIP AMs. Labour have suggested that there was a deal between these parties, but Plaid have denied it. I don't really see why it's a problem though as parties seen as left wing doing deals with right wing parties has never caused any friction in the past.

Joking aside, I do think the "deals" aspect of this is a red herring, Whether it's true or not I don't think Labour actually has any evidence for it. Interestingly, it does seem like one of the things that Plaid wants to push for in exchange for supporting a new Welsh Labour government is to change the voting system to the Assembly to something that more proportional (STV was mentioned). Having looked a bit more closely at how the Welsh Assembly works in practice I honestly find it very hard to not agree with them, the system does seem pretty dysfunctional to me.

In any case, if you feel like following some interesting government forming negotiations Wales is one to watch right now - current word is that Labour has offered a ministerial post to Kirsty Williams (Liberal Democrat AM), implying a minority coalition which would be a first in UK politics. Or we might see a change in electoral system in Wales or both of these things. Or, more likely, something more boring but maybe the process will be interesting.

London

How it works

The Mayor of London has an unusually large amount of executive power for a single elected politician in the UK - having powers to plan housing, direct transport policy and policing, and to accept or reject planning permission on a personal basis. Large projects by previous mayors have included the Oyster Card system, the Congestion Charge in the centre of the city, cycle hire projects and a ban on alcohol on London public transport - so this one individual can enact a lot of change.

The voting system used for the mayoral election is the supplementary vote (SV), which is a variant on the alternative vote (or instant runoff voting (IRV)) used in Australia and Irish presidential elections - which is in turn basically STV for where there's only one position to be filled. In IRV voters rank their candidates by preference and should no candidate win 50% of the vote then extra rounds of voting are simulated by eliminating the weakest candidate and redistributing their votes to their second preferences. The principle difference between IRV and SV is that voters only get to rank two candidates by preference and there are also two rounds of counting, with all but the top two candidates being eliminated after the first round and preferences redistributed.

The London Assembly is more of an advisory body than a legislature proper, unlike the other devolved assemblies. Its function is largely to generate reports on various issues, publish them and make recommendations to the Mayor of London - though it can also amend budgets or reject strategy proposals. It can only do this with a two thirds majority however so it is probably the least powerful devolved body. Like the others it runs under MMP, though with only 25 AMs total (11 list AMs). The one major way in which its voting system differs from Scotland and Wales is that it has a single list for all of London rather than regional lists.

The result

London Mayoral Election 2016

Labour's Sadiq Khan very easily won the mayoral vote. Zac Goldsmith (the Conservative candidate) actually started the campaign in a fairly strong position (according to polling which later correctly predicted the real result) but his campaign has been dogged by allegations of racism, from inside Labour and out, and of racial profiling of Asian voters. This rather overshadowed everything else, though there were also stories of anti-semitism within Labour in which Ken Livingstone, a previous mayor, was embroiled. Whether the Tory campaign was racist or not it certainly wasn't effective and it handed Sadiq a larger margin of victory than Boris Johnson ever enjoyed, and left Goldsmith 9% down on Boris' performance in 2012.

For the remaining candidates the picture in 2016 is not vastly different from 2012. UKIP and the Greens secured very modest increases in their first preference vote share, and the Liberal Democrats an even smaller increase. Siobhan Benita, an independent, had secured a strong fifth place in 2012 but did not stand in 2016, so UKIP effectively rose from sixth to fifth place. Generally the picture is more or less the same as it was in 2012, save for the lack of a strong independent and the decent showing of the previously unknown Women's Equality party (who gained over 3% of the vote). Given the Greens coming third in 2012 was seen as a big achievement this can probably be counted as a good result for them.

Sadiq Khan (Labour), Zac Goldsmith (Conservative), Siân Berry (Green) and Caroline Pidgeon (Liberal Democrat). Images from Wikimedia Commons.

London Assembly Elections 2016 (List Vote)

London Assembly Elections 2016 (Seats)

For the London Assembly the smaller parties generally got a bit more of the vote than in the mayoral election - particularly UKIP who were a clear fifth in the mayoral election but fourth by the tiniest of whiskers in the Assembly. However, the vote shares from the previous election had not changed very much for most of the parties involved - Labour, Greens and the Liberal Democrats all had marginal drops in their vote, there was a small (but noticable) drop in the Conservative vote and a slightly larger (but still small) increase in the UKIP vote. The Conservatives lost far fewer votes in the Assembly election than for the mayoral vote so presumably most of the blame for the poor tone of the Tory campaign was attributed to Zac Goldsmith himself. There was a bit of hype pre-election around the Women's Equality party, which ended up getting a fair chunk of the vote (3.5%, by far the most of the parties without representation) but not enough to put them in serious contention for a seat.

The results were a bit disproportional, as 10% of the vote went to parties that were unrepresented (understandable in a 25 seat chamber), but were internally consistent save for the Liberal Democrat result where they got only 1 AM for UKIP's 2, despite a gap in the vote of only 0.2%. Constituency wise the London Assembly, to be honest, is usually pretty boring. Merton & Wandsworth was a surprise Labour gain but otherwise nothing massively unexpected happened. UKIP also increased their voteshare by over 9% in Bexhill & Bromley, and Havering & Redbridge so some large swings happened but these are areas known to be UKIP friendly, in stark contrast to most of the city, so it is not hugely surprising that they would do well in these areas.

Overall London was bad for the Conservatives as their candidate lost, lost badly and lost in an undignified manner that marred his reputation - which had previously been one of a moderate. Even his own side attacked Goldsmith after the event, with a former Conservative MP stating that there's "no use in having a dog whistle when everyone can hear it" and his own sister criticising his actions. Meanwhile for Labour it was an unambiguously good outcome, with the highest margin of victory in the mayoral vote since 2004 and no obvious downsides to this result. If I were to scrounge for one it's that Sadiq Khan's constituency isn't rock solid for Labour so there's an outside chance of their losing a by-election next month, but I think that was priced in back when Sadiq was selected.

For the other parties the Greens and the Liberal Democrats were pretty much static (the loss of the second Lib Dem AM being a quirk of the system) and UKIP advanced a little. However UKIP's advance was very marginal across the city as a whole and isn't much to be shouted about (they've also been in the Assembly before, but lost their seats at the next election, so this isn't a historic advance either). Meanwhile the Greens' maintaining their narrow but firm third place was a decent achievement given that they could have easily been a flash in the pan in London elections.

London City Hall, where the Assembly meets. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

Other mayoral elections

London is a special case when it comes to English and Welsh mayors. The Mayor of London has special powers defined by specific legislation and also has the London Assembly to provide a level of checks and balances. Most mayors simply have the powers of the local authority they are voted into and take over the role of the executive committee used more commonly in councils. Some powers are designated as co-decision powers and can be rejected or amended by the council, but only with a two thirds majority.

Just to keep things simple the title mayor (or lord mayor) can also appear as an internally elected council role acting as the ceremonial figurehead for a local government - this role is not related to the role of an elected mayor. Bristol, for instance, has an elected mayor and a lord mayor.

Furthermore, as an elected mayor represents any council area there is nothing to stop quite strange uses of the term "mayor" from arising - for instance Copeland, a council area including substantial rural areas, has an elected mayor; and Tower Hamlets, part of London, has two directly elected mayors - the mayor of Tower Hamlets and the Mayor of London.

The elected mayoral model of local government has not been widely adopted (its not hugely popular with the public and tends to be actively unpopular with councils), but nevertheless some local authorities have opted to use it and three of these held their elections (by SV) on the same day as the council and devolved elections. These were Bristol, Liverpool and Salford. It's worth reiterating that these mayors cover the local authority area and not the urban area or metro area of the city - the mayors of Bristol and especially Liverpool have power over a smaller geographical area than you would expect given their titles.

Onto the results. As with the devolved elections I've presented results from 2012 to allow comparisons to the last cycle, I've shown first preference votes only (as aside from Bristol 2012 it's pretty clear who's going to win from the first round, the leads are quite crushing) and I've also excluded independent candidates. I was quite loath to do this especially as many of them did well and one (in Liverpool 2012) even came second but ... let's say there were quite a lot of them in some of these elections. The charts are already a bit too busy with minor parties, let alone independents as well!

Salford Mayoral Election 2016

Not the most exciting election in the world this. A very solid Labour area and the fact that a lot of parties that ran in 2012 didn't in 2016 means voteshare is up all around. I may be reading too much into this but the jump in the Conservative vote looks pretty substantial, though I think making up ground is a bit academic in an election like this. Unless there are major demographic changes in Salford or the Labour party suffer a catastrophic collapse akin to that of the Liberal party in the interwar years this mayorality is never changing hands! UKIP are up even more than the Conservatives, but they have advanced nationally since 2012 and would presumably have reaped most of the benefit from the English Democrats and BNP standing down - as they tend to attract ex-hard/far right voters. So perhaps this is unsurprising.

Liverpool Mayoral Election 2016

Liverpool is a bit more interesting, although the number of hard and far right parties in the 2012 election make the graph quite hard to read!

As can be seen the Labour vote dropped from overwhelming to merely crushing, the Conservative vote dropped a tad, the Liberal Democrat vote is up substantially taking them to a distant but very clear second (they were third behind an unpictured independent in 2012) and the Green vote is also up noticably, taking them to a clear third. TUSC remains where it was and the English Democrats are up a smidge, presumably taking the votes from UKIP, the BNP and the National Front.

I find it interesting that the dynamics of the city are clearly very different from that of England (even Northern England) at large, the TUSC (hard left) candidate actually gains a pretty decent share of the vote here and you even see the splinter Liberal party participating in the 2012 vote - a rare sighting indeed!

Anyhow. A very expected Labour hold but also a good night for the Greens and an even better night for the Liberal Democrats. The Liberal Democrats had control of the council for twelve years (though they had a poor reputation) but lost power in 2010 and were nigh on obliterated in Liverpool during the coalition years - being equal in representation on the city council to the Liberal party and behind the Greens.

So a firm second place in the mayoral election may represent themselves re-establishing themselves as the primary opposition against Labour in the city, big news for them. They also gained in the council elections (the Greens seemed to neither gain nor lose anything) and as Liverpool elects in thirds we haven't long to see if their good fortune in the city continues.

Bristol Mayoral Election 2016

The final election is Bristol, usually the mayoral election outside of London that gets most attention. Out of the three elections here this was the only one that you could really say was competitive and where there was any real doubt about the result before the actual election.

Bristol 1st, the vehicle for (essentially) independent George Ferguson, had won the 2012 election (netting me some money in the process courtesy of Ladbrokes) with Ferguson proving to be a very active, but controversial mayor. Come 2016 and it's clear that he still had his fans, but the first preference votes indicated that the pendulum had well and truly swung to Labour and on the second round Labour gained the mayorality.

Bristol 1st was (is?) only a vehicle for Ferguson but the Labour result, in conjunction with the local election results represents the end of a journey for the city from a Liberal Democrat heartland to a Labour stronghold (yes, coalition), with Labour gaining both the mayorality and majority control of the council in these elections (taking seats from every other party on the council). There's even almost a nice symmetry about it, with the Liberal Democrats having 38 councillors in 2010 and Labour having 37 in 2016.

At the risk of spoiling the section on the local elections this is not the usual pattern across the country. Broadly speaking the Liberal Democrats did pretty well (though it's complicated) and Labour ... did not (though it's complicated). But this is a reminder that no matter how the wind blows across the country that there will be places having their own eddies going the other way.

Salford, Liverpool, Bristol. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

Local Elections

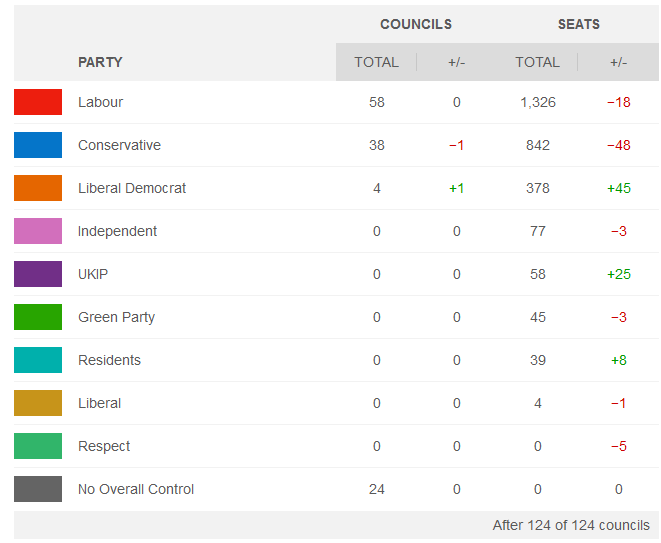

The local election results (from the BBC) are as follows:

These results are aggregated and hide details of where support was gained and lost (which I'll cover later) and it also therefore follows that the control of councils is a bit more complex than it looks. Labour lost control in Dudley but gained control in Bristol (net zero), the Conservatives gained control of Peterborough but lost Elmbridge and Worcester, and the Liberal Democrats gained Watford.

If we ignore the context of this vote, and the associated scales of seat changes that we might expect, then on the face of it this looks like a very good result for the Liberal Democrats and also a pretty good one for UKIP. It looks (and is) terrible for RESPECT, eliminated from local government and the results look pretty static for the Greens, though this does hide a pretty bad result, which I'll discuss later. For the Conservatives the results look very bad and it doesn't look great for Labour.

But this is without context. If we want to add some then we can compare the results with the Rallings and Thrasher projections of local elections (which tend to have a good record), in turn based off the recent local by-election history (which I have mentioned in a more qualitative fashion in previous posts). These projections were only made for four of the five main parties and were:

Conservatives: gain 50 seats.

Labour: lose 150 seats.

Liberal Democrats: gain 40 seats.

UKIP: gain 40 seats.

So Labour substantially beat the projection, the Liberal Democrats beat it by a bit while the Conservatives substantially undershot the projection and UKIP underperformed by a moderate amount.

However these projections are based off past performance. Beating a projection could mean that you're doing awfully earlier in the year but manage to pull things together to do merely badly, or it could mean that you're doing well during the year but don't quite hold it together. Or anything in between. So another metric of success must be considered: comparison with previous similar elections.

The projected national vote share, an estimate of the support across the whole country based on a non-representative subsect of council elections (Rallings and Thrasher also work out the national equivalent vote, which is a similar idea), for these 2016 elections were as follows:

2016 Local Elections // The projected national share alongside the vote share in authorities contested: pic.twitter.com/Av3RuV8eNI

— Britain Elects (@britainelects) 10 May 2016

As can be seen all of the three major parties actually lost votes compared to the previous round of these elections in 2012, so perhaps no-one should be too pleased. But the big loser compared to last time was Labour - vote share does change throughout the electoral cycle but this set of local elections is typically a high point for the opposition vote, which it clearly isn't this time around.

Although we can't compare like for like with these local elections for UKIP, as their projected national vote share was only calculated from 2013 onwards, they failed to improve their voteshare from recent local electionsand are down 10% from their high point of 2013. Despite their gaining councillors this may indicate stagnation or even decline. Or UKIP activists might just be distracted by EU referendum campaigning and maybe they'll do better next year, as others have suggested.

That Labour's voteshare is so far down is particularly obvious when comparing the 2012 and 2016 results in terms of seats, although these are not the exact same set of councils up for election there is a very significant overlap and the elections are broadly comparable. Yet look at the results:

Change in Councillor Number 2012 vs 2016

Change in Councils Controlled 2012 vs 2016

Yes, Labour massively outperformed their projections but these are still historically awful results and it's really quite unusual for an opposition party to be losing councillors in local elections that don't co-incide with the general election. That the Tories didn't gain and underperformed against their projections is a pretty sparse silver lining for Labour, on a typical night you wouldn't be contemplating the government party advancing in local elections at all. Even Iain Duncan Smith, a famously unsuccessful Conservative leader, managed substantial seat gains at the equivalent elections when he was opposition leader!

You can also throw water on everyone's results of course - the Liberal Democrats were the clear winners in terms of numbers of councillors elected but they lost a lot more last cycle than they gained this time, the Conservatives failing to gain indicates that they're probably not actively popular. But there are good reasons for the results for these parties being as they are.

The Liberal Democrats lost a lot of their reputation, and a lot of their previously core vote during the coalition years. Expecting them to regain support at the rate they lost it only a year after coalition and with greatly decreased media coverage is fantasy politics. It's about as likely as a magic dragon sweeping down to pick up Tim Farron and crown him King of the Mountain. The question of whether it's a good enough result for the yellows is (very) valid, of course, but expecting a recovery as metoric as their fall was precipitous is a bit much.

Meanwhile the Conservatives are the government and in this set of local elections you would expect them not only to lose seats but to haemmorage them. The government usually gets a bit of a beating in the first couple of sets of local elections after a general election, and this is barely a tap on the shoulder by comparison to what normally happens. And the greatest advantage of being the government is that even if people aren't enthusiastic about your party it doesn't matter if the public aren't enthusiastic about the opposition. You don't even need to be popular if no-one else is - just look at Thatcher's first government.

For Labour, on the other hand, there are no good excuses. Large council gains are the norm for the opposition at this set of elections and even Ed Milliband, who was consistently less popular than his party and did pretty poorly in 2015, gained hundreds of councillors at the equivalent set of elections to this. Tony Blair gained over a thousand when he was new. I can understand people who are Labour supporters wanting to put a brave face on this but these results are just historically very, very bad - 1980s bad. Optimism can't overcome the reality of genuinely concerning results and even though the (dire) predictions were exceeded it's difficult to see Labour winning, or even progressing, in 2020 at this rate.

There is one more metric we can consider when thinking about these elections - what the parties themselves wanted to achieve, this means geography. Local government results, in most of the country, impact a lot on results in the general election. Certainly there are exceptions: Labour is dominant on Nuneaton council but was unable to win the seat, Watford is an area where the Liberal Democrats have a long history of success but where that has never translated into actually winning the seat in parliament, remote parts of Wales and Scotland often dispense with the party system altogether in local elections but don't return independents to Westminister.

To a degree Labour and the Conservatives (and a to a lesser degree UKIP) just want nice seat tallies as a rising tide raises all ships. But not all gains are equal, gains in an area containing a nice marginal consistuency are certainly more valuable than the Conservatives getting more councillors in, say, Tunbridge Wells where their parliamentary seat is unshakable.

For the Liberal Democrats and Greensthey operate mostly by targetting seats and wards so getting the right seats in the right places is critical for their survival and success. Of course they want more seats but it's almost better to have fewer seats but in good places than to have a nice looking total on the tally. I must admit that a more detailed look at the geographical aspects of the local elections could be a large post in itself, and that what follows is more a set of impressions than a quantitative study so do feel free to take a pinch of salt with the rest of this section.

Between Labour and the Conservatives, the picture is mixed in terms of important geography - for instance the Conservatives have done well in the council covering the key swing seat of Nuneaton as well as in council areas such as Derby or Coventry that contain other marginal seats. On the other hand other councils containing marginal seats such as Wolverhampton and Birmingham actually saw Labour retrenchment.

Although Conservatives had good fortune in many Labour-facing areas the same cannot be said in areas of Liberal Democrat or UKIP strength. Here they mostly remained static or fell back, which does suggest to me that there's not much enthusiasm for the Conservatives and that Labour losses may be more to do with disenchantment with the reds than any interest in the blues.

This isn't to say that Labour have done badly across the board as there have been very solid defences in certain areas of strength - both in metropolitan strongholds like Bristol or Oxford but also in some areas which contain more marginal seats (mentioned previously). Labour also held up very well in many, but not all, wealthy metropolitan areas where they faced Liberal Democrats or Greens, perhaps correlating with where Corbyn is most popular, often gaining substantially in those areas. The picture is a bit more mixed in areas in the north of England (for instance Burnley seemed to move away from Labour to the Liberal Democrats) and Labour didn't hold out well against UKIP in the north of England at all. However, unless I missed something these losses were in Labour fortresses rather than anywhere particularly marginal. In terms of the main fight in 2020 the geographical spread of Labour losses and gains don't look hopeful, but the elections aren't without any positive results.

The Liberal Democrats had a patchy distribution of gained seats but also had (mostly modest) recoveries in many areas of previous council or parliamentary strength such as Sheffield, Burnley, Hull and Maidstone; had the only net council gain of the elections; and tended to entrench in areas they were already strong. Normally entrenchment in strong areas is not desirable as it implies piling up votes in seats that are already "in the bag" rather than gaining new ones - but some of these areas of entrenchment are actually in Conservative held seats that were unexpectedly lost in 2016, such as Cheltenham and Eastleigh. As such, these results are actually very positive for the Liberal Democrats and may bode well for 2020 in those seats (if the boundary review doesn't negatively impact their targetting too badly).

These positive results are not universal though and the party failed to advance, and even fell back in, some areas where they had been strong and may have hoped for recovery (usually areas Labour did well in) such as Newcastle, Bristol and Three Bridges. There were also some gains which, although I'm sure are welcome in their own right, are in areas that are are either not of particular interest to the party (such as in Rugby) or are in councils so dominated by Labour that their opposition is likely to be fairly token (such as in Sunderland and Manchester). So there's a limit on how rosy a picture can be painted.

For the Greens the details of where seats were won and lost are concerning. Although they seemed to make big advances in Solihull most of their gains were scattered around across many local authorities, rather than being concentrated in any one place. Moreover, most of these council gains were in areas where they did not already have many (if any) councillors - making it far harder to work up these areas into regions of Green strength.

In contrast they actually lost seats in areas of particular interest to the party - outside of Brighton Pavillion their best hopes for parliamentary seats have been in Norwich and Bristol, but they lost seats in both of these places. They also fell back slightly in other areas that they had traditionally been seen as reasonably strong in, such as Oxford. Generally Green local results have not been good from the geographical point of view, even if the total change in seats is unremarkable either way.

UKIPs results tended to be clustered a bit more optimally as there were some councils where they gained a few seats at once - Adur, Basildon, Great Yarmouth, Rotherham and Hartlepool are examples. If they can refrain from their famous UKIP infighting then these are areas they can try and cultivate into strongholds in the long term. Perhaps most hopefully for them they made major advances in Thurrock, the parliamentary seat of the same name having UKIP in a very strong third place. So even though UKIP seat gains were less than projected and UKIP tacticians must be worried about their projected national vote, their silver lining is that at least many of their seat gains were in useful areas to them.

All this can be yours! Nuneaton, Bristol, Watford, Norwich, Grays (in Thurrock). All images from Wikimedia Commons.

Overall I would say that it has been an acceptably good night for the Conservatives in local elections, despite the losses; it's generally been an extremely bad night for Labour but they proved good at defending territory they already had and beat their (admittedly dire) projections - small silver linings; it's definitely been a good night for the Liberal Democrats, but is it enough for them to regain their strong third place anytime soon? Greens had a subtly bad night as their seat losses were minor but they were largely replacing desirable seats with less useful ones. UKIP gained seats and gained them in useful places, but failed to meet their projections and also demonstrated their joint lowest projected national vote share. As stated previously this could be distraction or lack of steam but seeing their performance next year will be interesting either way.

As a final aside I also looked up the results for places I've lived in the past, just out of curiosity. If, like me, you're uncool enough to want to do this for yourself then there's an excellent spreadsheet of results online compiled by Britain Elects, which I relied on for a lot of this post in general, and a service by the Ordnance Survey which can tell you which ward your old addresses are in.

To be honest, I'm not a great advert for doing this as the results for my old addresses are mostly pretty boring (three Labour holds and a Liberal Democrat hold), except for one old address where the Greens gained a ward from the Conservatives in a fairly unlikely council. Mildly interesting to me - but maybe not to you!

Parliamentary By-Elections

There were two parliamentary by-elections held on the same day as the local and devolved elecitons. These were for the seats of Ogmore, and Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough, both are rock solid Labour seats and the former MPs had won these seats with a majority of the votes in 2015. A majority meaning an actual "over 50% of the vote" majority - these are real strongholds.

With that it mind it will absolutely shock you to hear the surprising news that these were ... easy Labour holds. In Ogden the Labour candidate pretty much maintained his position relative to the 2015 result, while in Sheffield the Labour candidate added almost 6% to an already hefty vote lead.

Ogmore By-Election

Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough By-Election

The results of the other parties are as follows: UKIP, the distant runners up in both seats, gained a tiny amount of ground in Ogmore and lost a larger but still small amount of ground in Sheffield. The Conservatives lost a small to moderate chunk of the vote in each election, moving down to fourth place in each. The Liberal Democrats stayed completely still in Ogmore, with a derisory share of the vote, and gained a tiny amount of the vote in Sheffield to emerge with a merely below average share of the vote (though regaining third place). Plaid Cymru gained a decent chunk (5.5%) of the vote in Ogmore and moved to third place, within half a percent of second place, while the Greens ... were present at the Sheffield election.

Not hugely interesting or informative by-elections and easy holds both. Maybe UKIP would have wanted to advance meaningfully in both seats, maybe the Liberal Democrats would have liked to have done so in Sheffield but neither of them got what they wanted. There's really nothing more to say.

Some pictures from the constituencies. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs)

Perhaps my most controversial opinion in politics is that I don't really agree that police chiefs should be elected. Shocking, I know. I realise that this may be a bit iconoclastic for some but please put down your pitchforks and burning torches in order to give me time to drop my unsubtle sarcasm and to briefly(ish) describe what actually hapend in the PCC elections (held under SV):

Police and Crime Commissioner Election Results

As can be seen in this election both Labour and the Conservatives made gains. This was largely at the expense of the wide variety of independent PCCs elected in the last cycle (though the big two parties did also make gains from each other as well). Plaid Cymru also broke through in these elections and won two of the four Welsh constabularies (one from a Conservative, one from an independent), the first third party to win a PCC election. There was a bloodbath of independents.

No other parties won any posts, which is understandable given that the Liberal Democrats and Greens both tend to have quite localised support (not suited to the large PCC constituencies) and UKIP are probably just a bit too far from the political centre to attract many second preference votes, I would imagine. These elections are not held in Scotland or Northern Ireland so the SNP and NI parties don't really have a horse in this race to begin with.

The only other feature of note of these elections were that turnout was pretty subtantially up across the board from last time, albeit from one of the (if not the) least well attended large-scale elections in UK history. In England this means mostly turnout in the 20% range, with a few constituencies having turnout above 30% and a few below 20%. This is still a terrible turnout, just less terrible than last time - presumably because they have been held alongside council elections in much of the country.

For context half of the English PCC constituencies had a turnout below that of the European election with the lowest UK turnout in history (24%), one of them had a turnout below the by-election with the lowest peacetime turnout since 1918 (Manchester Central - 18.16%) and none of them had a turnout above that of the most recent European elections (35.6%). So these are not popular elections.

Wales, however, was a different story and the turnout there was actually healthy and even noticeably higher than you would get in European elections (though much less than in general elections), even approaching 50% in one constituency. Presumably an effect of the Assembly elections occuring on the same day?

With these elections it was a good night for both of the main parties, and a particularly good one for Plaid. The other parties were all no hopers for actually winning a PCC but there didn't seem to be many lost deposits either. I don't think these elections have much significance beyond themselves, so I don't think any party activists should get too excited over these results.

The elections were bad for those who think these positions should be non-partisan (due to large losses of independents) and bad for bitter people like me who get schadenfreude from bad turnout at PCC elections!

Party by Party Overview

The Conservatives had a quietly decent set of elections, their losses in Wales were minor and although they lost dozens of council seats and failed to meet their projections in local elections they still had a pretty light drubbing considering the stage in the electoral cycle. Their biggest success was in Scotland where they stormed to second place, and their biggest failure was in London where they ran a very poor campaign marred with allegations of racism. It does not seem as though there's much enthusiasm for the Conservatives, save perhaps the moderate Scottish variety, so they should not rest on their laurels. Nevertheless, a very decent result - especially considering the party's long term plan seems to be to tear themselves to shreds over Europe.

Labour generally performed poorly but less poorly than had been predicted. Their local election results were dire but not the catastrophe that had been expected and they held steady in Wales, but largely due to the vagaries of the voting system disguising a sharp drop in their vote. In a nice symmetry they had an unrelenting nightmare in Scotland but a well-run and very successful campaign in London, providing a bit of light for an otherwise gloomy set of elections. Overall the signs for Labour in 2020 are not good, four years is a long time but Ed Milliband performed far better than this and still didn't win the general election. However, they may prove resilient in some areas where they are already successful, based on the local elections.

The Liberal Democrats performed well at the local elections and their only disaster (Wales) was more to do with the voting system than the actual votes cast, but did they perform well enough? It's hard to say that there's much evidence for a substantal recovery in Liberal Democrat votes but they have certainly done well in getting their vote more concentrated where it matters (outside of Wales at least) which, barring electoral reform in Westminister, will be the only way they can hope to grow.

For the Greens I think it's hard to view these results as anything other than a step back overall, save in Scotland, London (and to some extent NI) where they certainly did well. Although technically the Scottish Greens and NI Greens are totally distinct from the English and Welsh party. In the local elections it did seem like the Greens had largely lost seats that would be useful for building future local government bases, and possibly even winnable parliamentary seats, in exchange for fairly random scattered seats across the country. It's hard to see much growth in the short to medium term for the Greens, as a lot of avenues for this seem to have closed for the time being, but they are still far stronger than they were a decade ago.

UKIP appeared to go nowhere in Scotland and Northern Ireland. but came onto the Welsh scene in a with a decently big splash (having not been much of a force outside of European elections in 2011), albeit a smidge weaker than they had reason to expect. In the local elections they made gains in the right places but failed to meet their projections and, although we haven't yet had a cycle of UKIP's equivalent vote share in local elections, they have failed to advance in local vote share since last year - which was itself a low for the party. In a fairly conservative reading of their fortunes I would say that it looks like they are holding steady but not really advancing in appreciable ways, save in Wales.

Finally, the nationalists. The SNP performed exceptionally well and it's hard to see sign of an unwind in their popularity, even if they are disappointed in not maintaining their majority. Plaid Cymru, on the other hand, seems to be doing successfully enough but without much advancement.

Proportionality

I also wanted to work out how proportional the MMP and STV elections were this year. A quick overview of how to quantify proportionality can be found here, as well as a record of proportionality of UK general elections. I used two of these indices, the Loosemore-Hanby index, because it is used by the Electoral Reform Society, and the Gallagher index because it's taken more seriously in academia. I didn't bother with calculating the Sainte-Laguë index because I'm lazy. The vote share percentage used for this is the first preference vote for Northern Ireland and the list share votes for the MMP elections as these would presumably be the vote shares least affected by tactical concerns.

Loosemore-Hanby and Gallagher Indices of Disproportionality

As can be seen clearly by either index the Welsh election performed pretty poorly for an election under a supposedly proportional system. Quickly scoping the results two likely contributors to this are Labour, who lost only 3% of their AMs (i.e. 1) for a 5.4% drop in the list vote, and the Liberal Democrats who lost 80% of their AMS (i.e. 4) for a 1.5% drop in the list vote.

Scotland and Northern Ireland, by contrast did pretty decently and had results typical for proprtional systems that aren't pure party lists with no thresholding. A list of Gallagher (least square) indices of world elections exists online for international comparisons. Northern Ireland did "better" by the Gallagher index by a whisker, and Scotland did better on the Loosemore-Hanby index by a nose. It is worth noting that Scotland's election this year was unusually proportional, and Northern Ireland's unusually disproportional by their historical standards.

Meanwhile London's proportionality was somewhere between but closer to the fairly proportional Scottish and Northern Irish results than the non-proportional Welsh ones. This is a result of the Liberal Democrat result (again), where they won 0.2% less of the vote than UKIP and had one AM instead of the two UKIP had. I actually double checked this on my spreadsheet where I worked out the Gallagher indices. Adding another list seat, keeping vote percentages the same, and adding it to the Liberal Democrat tally (as it would have likely gone had it existed) gives very similar proportionality figures to the Northern Irish result.

So not to beat my electoral reform drum too hard here but given these systems are all supposed to be proportional there probably is a need for some refinement of the systems except perhaps in Northern Ireland. Wales' election was particularly bad this time around, but it's never had a good year for proportionality - its Gallagher indices have been consistently very high for a proportional system and it needs a major shake-up. Scotland had a very good year for proportionality but its historical record is not so good, albeit better than Wales', so it could probably use a bit of polish.

In both cases, making the assumption MMP is retained, there are some obvious tweaks. Abolishing regional lists in favour of national ones (this would also be a good idea for European Parliament elections) and increasing the number of list members, ideally to match the number of constituency members, would have a major positive impact. More minor improvements could be delivered by dealing with overhang seats differently and adopting Sainte-Laguë for use in the list component of the system to reduce the overrepresentation of major parties.

In London there are no regional lists and although there are fewer list AMs than constituency ones. It seems as though the system is already pretty decently proportional but perhaps just adding more seats across the board would be a good idea. Should the Liberal Democrats remain in the doldrums and the Greens and UKIP maintain their level of popularity then the last list seat allocated is going to going to remain hotly contested and a large source of disproportionality, more or less randomly docking a seat from one of the three parties for tiny vote share differences.

A post-script, six months on

I became aware of an error in my spreadsheet for the Welsh Assembly results which vastly increased the disproportionality relative to the real result. I therefore corrected the data (the previous Loosemore-Hanby index was at 25.8 and the previous Gallagher index was 15.1) and removed the following sentence as it did not reflect the actual data: "It was even slightly more disproportional than the general election of last year, which was run under a majoritarian system and which was seen as very disproportional even for UK general elections run under FPTP."

Corrections made 30/11/16 on post originally published 14/5/16.