Representation versus democracy: the impossibility of perfect democracy

I've recently been thinking about the nature of democracy and how perfection within it is more or less impossible. Some aspects of it largely come down to personal choice: popular or liberal democracy? Presidential or parliamentary? Obviously you can't please everyone even if the answer is clearly liberal parliamentary democracy!

But there is, in fact, a simple problem of arithmetic that means that with most sets of real voters it's impossible to have an absolutely perfect democratic result. I also think that you usually can't have perfectly functioning representation. And also that ideal representation and democracy, to some extent, work against each other.

This sounds pessimistic but I have my reasons for thinking this.

Starting from first principles the main distinguishing factors in voting systems, and therefore in the nature of both democracy and representation, is whether the system is majoritarian or proportional. This is not actually very black and white in practice - for instance Chile's proportional list system using separate seats only electing two representatives is a very unproportional proportional system (by design) and many countries (particularly in Eastern Europe and the Far East) use so called semi-proportional systems. And sometimes even firmly majoritarian systems can deliver coalitions, and firmly proportional systems can result in a two party chamber.

Flags of countries with proportional systems that aren't very proportional, or majoritarian systems that aren't very majoritarian. Pictures from Wikimedia Commons.

However, for the sake of a simple thought experiment let's imagine perfectly proportional or majoritarian systems in a case where you had party A gaining 31% of the vote, party B gaining 20%, parties C-F gaining just 10% each and party G getting 9%. In either case you have a situation that could be potentially considered undemocratic.

Under the majoritarian system we have less than a third of the votes probably giving one party over half the seats and almost all the power - UK general elections have yielded a majority on 35% vs 32% of the vote so this is not far fetched. Even at first glance it's quite hard to call this democratic - what is firmly a minority decided who is in power and the 69% of the public who didn't care for party A have no say. Majoritarian systems also tend to have issues with producing safe seats, making some results foregone conclusions, and with massively underrepresenting smaller parties so the 49% of people voting for parties C-G likely have far fewer seats than 49% to show for it. More geographically localised parties can, however, buck this trend to some extent - as can be seen if you calculate the proportionality of results for Plaid Cymru/SNP versus Liberal Democrats/Greens/UKIP in recent UK general elections or if you follow the fortunes of regionalist parties in Indian elections.

If we have these same results (A: 31%, B: 20%, C-F: 10% each, G: 9%) occuring in a proportional system we have a situation that can also be called undemocratic, though in my view in a much less blatant and much more subtle way. Party A cannot simply ignore the views of the 69% of voters that didn't vote for it, but it must form a coaliton (or some looser deal) to run the government and therefore the government policy that results is not what people voted for but rather a compromise between the views of party A voters and some, but not all, of the rest of the electorate. Moreover, the nature of the compromise is not directly due solely to their vote shares.

Firstly some parties may get on better than others. In the UK it's easier to imagine Labour going into coalition with the Greens or (even post-Clegg) the Liberal Democrats than with the Conservatives, in Italy pre-1990 many coalitions were formed with the sole purpose of not including the Communists - so in this hypothetical election party A can form a coalition with party B or with a combination of multiple third parties but you can be sure that one of these arrangements will be more favoured than the other by party A. A big part of what compromise emerges depends not solely on but on ideological similarity and personal connections between people in different parties. The coalition does not have to include the second most popular party or seek to include as many parties as is viable to seek the widest pool of views for a compromise. In fact I picked the numbers I did because these needn't even include party A - parties B-G could form a perfectly viable coalition and, although it's rare, coalitions excluding the most popular party have existed. So the policy of a government doesn't reflect the views of merely 31% but it is not a compromise between the views of the entire electorate either, and whose views are included in the compromise can be due to factors outside voters' control or highly situational. It needn't even relate to voteshares, save that 50% can be reached.

Then the details of the deal must be hammered out. Will an A-B coalition result in policy that's around two thirds from party A and a third from party B? Of course not - coalition (including negotiations) is both collaboration and competition and there's a degree of powerplay. A masterful negotiator can wring a more favourable compropomise and a naïve or weak minded one can play their cards poorly and come back having given away far more than is reasonably. Beyond this some legislation matters more than others, so the compromise will never exactly match the preferences of the electorate.

So no matter what the system unless you genuinely have 50% of voters plumping for the same party then perfect democracy is impossible, although the problems with the proportional outcome are more minor in my view. Even in this circumstance however there is the old cliché that "all parties are coalitions" that throws a spanner in the works. What a "big tent" party stands for varies over time far moreso than a smaller party and people may be voting for different wings within it. If Jeremy Corbyn and Tony Blair are not on good enough terms to shake hands and Labour somehow wins 51% of the vote then are the Corbynites and Blairites really voting for the same thing? In one sense yes, but in another no.

A final aside is that most countries don't have preferential voting and therefore have a very crude method of assaying the public's opinions. Most people don't have one favoured party with the rest equally disfavoured, a voter may like two parties more or less equally and be forced to give all their support to one over the other fairly arbitrarily, a voter may have a clear preference for one party but hold a particularly high or low regard to specific others. Not taking this into account means that even substantial nuances in voter opinion are ignored by the system and although preferential voting is not a perfect way of taking these kinds of subtleties in voters' views into account it is at least better than not attempting anything.

Preferential voting aside, the real issue with democracy basically boils down to that any number below 50 is below 50, and nothing can change that. Every system is undemocratic to some degree, but some are a lot less so than others.

In contrast the issue with representation is more philosophical and less to do with a arithmetic. What is representation and how do you achieve it?

The system in the UK was originally intended for seats to represent communities rather than the people, this is outlined here. It is why it was deemed acceptable for the sizes of seats to vary wildly during the 19th century, why Old Sarum could have a constituency and Manchester couldn't. Obviously the idea of representing the people has now been incorporated to some extent into the system, with there being limitations on the population of a constituency. The old way of doing things was untenable.

Thriving metropolis! It's a travesty this place lost its seat. Pictures from Wikimedia Commons.

However, although the idea of a constituency being a community allowed some blatantly undemocratic practices in the past there is a kernel of wisdom in it. What does a representative represent? If they represent something incoherent then what is the point?

And herein lies some of my problems with the current system. Many criticisms can be levelled at first past the post for its less democratic features but a less voiced problem lies at the heart of its supposed greatest virtue: the constituency link. To have even the pretense of democracy you need to have approximately similarly sized constituencies, but to have even the pretense of real representation you need to have constituencies match geographical communities. These requirements are sometimes completely at odds with each other and constituencies often slightly shift each electoral cycle to keep the populations within acceptable bounds - an odd concept to square with the idea of representing with a community! Why is that half of town part of that community in 2010 but part of the other one in 2015?

An example of how the system does not produce good boundaries for representation is Oxford, so this will be used as a case study. If I look at the city of Oxford I can see two seats that embody the flaws with the strange compromise we use for constituencies. It has two constituencies: Oxford East, and Oxford West and Abingdon.

As the name implies, the latter seat isn't entirely in Oxford. As the name does not imply, most of west Oxford (which includes the city centre) is not part of the constituency. The seat comprises the very coherent community consisting of north Oxford, areas to the west of the train station, part of (but not all of) the Osney and Jericho areas of the city, as well as a vast swathe of villages, small towns and countryside to the north, west and south of the city as well as the poorly named "Oxford London Airport". This wonderfully coherent community therefore also has a Conservative MP, despite the city it takes its name having no Conservative councillors (though as of 2016 it's no longer a special snowflake in this regard, the town of Watford is in the same boat).

Sadly Oxford East isn't quite so simple, sensible and logical as the other seat. It's confusingly actually entirely within the city boundaries - though common sense at least prevailed in some areas, as the west of Oxford is mostly in Oxford East.

Hideously unsubtle sarcasm aside, the seats for the city embody two of my pet peeves. Split rural-urban seats (usually arising because an urban area has too many people for one seat but not enough for two) and splits within cities that don't make any sense if you are familiar with the city. While you certainly get less coherent constituencies abroad, the Oxford seats are pretty bad by the standards of the UK.

These are all in the same constituency, except for the half of Little Clarendon Street that apparently is not. Perhaps being a bit mischevious as some parts of Oxford itself look like countryside, but the point is made. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

Rural and urban voters are two obvious groups that can have very different needs and where it is hard to see one person representing both fairly - is the Oxford West and Abingdon MP supposed to push harder for the farmers or the workers in the city? A rural voter might need more money put on roads and lower fuel duty, while an urban voter might need more money from fuel duty towards buses (via council money) and trains. Urban and rural voters can have very different needs and certainly different wants, particularly in places like Oxfordshire with a left-wing city in a right-wing county. This is quite a common issue with UK constituencies - some other examples of seats on the edge of cities that seem to be mixed urban-rural include Sheffield Hallam, Romsey and Southampton North, Coventry North West, Cardiff West, Brighton Kemptown and two Edinburgh seats (West Burgh, South West Burgh).

Illogical splits in cities do bother me as well. It makes sense for Oxford to have two MPs given its size and despite it being seen as (and largely being) a rich city it does have some areas in the east that are actually very deprived so an east-west divide is probably the most logical. Areas of the city also have very different characters to other regions of the city - Cowley (in the east) in particular feels like a completely different town altogether, quite apart from Oxford even though they are contiguous. You can't just draw a line down the city and get a perfect boundary dividing up places that "feel" similar, and that may be a bit of a subjective measure anyway, but there is a broad east-west divide and there is an obvious boundary between the east and west of the city. This is, in my view, on the river Cherwell.

Unfortunately the actual boundary for the constituencies is further west and completely arbitrary. One half of one of the main shopping streets in the Jericho area is in one constituency, the other is in the other one. The train station is in Oxford West and Abingdon, the parade of shops near it is in Oxford East. Worcester College is in Oxford West, the flats and shops on the other side of the road of it are not. The pub The Oxford Retreat is in Oxford West, the buildings beside and behind it are in Oxford East. The University Parks cross the constituency boundary et cetera.

Why does whoever lives above The Oxford Retreat have a different representative to their neighbour who lives above the Lebanese restaurant? Are the students living in Worcester, Somerville or St Anne's Colleges fundamentally part of a different community to those in Christchurch or St. Hilda's? Do two young, middle income people in different flatshares one in Botley (West), one in the centre (East) have less in common with each other than they do with, say, a farmer living near Cumnor (West) or a desperately poor man living in council housing in Blackbird Leys (East)?

To some extent I'm being mischievous. You cannot completely iron out these differences, and some of the criticisms I made still hold even if the boundaries were sensible. A flatsharer in Jericho (should be West) and off the Cowley Road (should be East) may well have interests that are very aligned, but the owner of a large detached house in Headington (East) may have different interests to the previously mentioned man in Blackbird Leys (East). Nevertheless these effects are reduced somewhat, and if the logic of communities is to hold then it would make sense to assign the constituency to some area that makes sense to the people living there - East Oxford may contain a lot of variation within it but if you use the term "East Oxford" most people familiar with the city will have a very similar idea of what parts of town are meant by the term.

This said I'm not a fan of dividing cities up any more than necessary even if the division makes sense, a badly placed boundary can ruin a party's electoral chances by accidents of geography. Oxford in the 2010 election produced a Conservative and a Labour MP. As briefly touched upon before the Conservative party has no representatives in the city council (and hasn't for 16 years at the time of writing), so this is an odd result at first glance.

Moreover, between the two seats the Liberal Democrats actually did the best overall - had there been one "Oxford and Abingdon" seat they would have comfortably won it with a 7% lead over the Conservatives. It is difficult to say whether they would have won a single Oxford only seat, but their lead over Labour (their main competitor in the city itself) in the hypothetical combined constituency was large enough (12%) that it is at least a strong possibility.

Combined Oxford Seats 2010 Results

Despite "winning" in the area, the party won no seats in Oxford. This is because Liberal Democrat support was at the time largely concentrated in the centre of the city, split between both seats. The boundary affected the election result quite profoundly and a slightly different line on the map could have changed the result in at least one of the seats. This was far less applicable in 2015, as coalition had damaged the popularity of the party and its remaining areas of strength were still split between the two constituencies but not along the border itself. Nevertheless, for that one election cycle the very presence of a boundary had a massively distorting effect - the community of Oxford seemed to favour the Liberal Democrats, but the arbitrary placing of people between two constituencies meant they did not get a Liberal Democrat MP. Perhaps readers who are particularly unfriendly to the Liberal Democrats won't shed any tears over this, but this is just a case I happen to be familiar with as I lived in the city when it happened - doubtless there are cases that occured in other areas and with other parties getting "unfairly" penalised by an unfortunately and arbitrarily placed boundary.

We can generalise and say more even constituency sizes are (probably) more democratic under a first past the post system (obviously evening out constituency sizes to make it more democratic is like putting a plaster on a severed leg but still...). But there is a tension between democracy and representation here. If the MP is to represent a community (and who are they representing if not?) then clearly having more even constituencies makes it more likely that a constituency does not coherently represent a community - as geographic communities are not of equal size themselves. As the Oxford examples show trying to square this circle can sometimes even result in the "wrong" representative for a community when a popular party has support clustered near a boundary and I would imagine this isn't a massively uncommon occurance.

Many problems with constituencies can be reduced by simply having far more of them as this makes the result a bit more proportional and you're less likely to get boundaries affecting the result or mixed urban-rural seats with smaller constituencies (and you're more likely to be able to formulate a constituency that makes sense to the people living in it). We can see this if we compare the composition of councillors in Great Britain to MPs and to the general election voteshare. There are, of course, a number of caveats: there are (many) smaller parties that only run in local elections, council elections are staggered through an election cycle anyway and, most importantly, people don't always vote in the same manner in council and general elections (though the correlation is usually pretty close). For instance, the largest party on Ceredigion council is Plaid Cymru but the MP is a Liberal Democrat and there are councils in Scotland and Wales which are independent dominated but still elect party MPs. This said the national equivalent vote (an estimate of what the percentage of the vote in a local election would be if it were held across the entire country) was near identical to the general election vote percentages in 2015 - though of course not all councillors are elected in general election years.

With all these caveats if we look at the number of councillors in principal authorities as of May 2014 and the number of MPs elected in 2015 it's notable how much less disproportionate the results are. Here's a graph demonstrating this for the five biggest UK parties. The Liberal Democrats actually have more councillors than is proportional (slightly), in stark contrast to their MP count. Meanwhile the Conservatives and Labour's disproportionately high amount of councillors is nevertheless less disproportionate than their number of MPs. Proportionality between votes and seats for the Greens and UKIP remains comparably poor on councils, but slightly less badly so.

Difference between percentages of the GE vote and percentages of MPs or councillors

On the other hand there are over 20,000 councillors for Great Britain and that is far too large a number to have for MPs! Clearly just increasing the number of seats this far this isn't a viable solution, and there are still some major issues with proportionality even at this level.

Another question, linked to this, which I think is relevant to the role of voting systems on representation is whether or not a single person can even decently represent a community. A community is not some monolithic mass, it consists of its people and contains people with wide viewpoints even in the heaviest party strongholds - stereotypically left-wing Islington will have some conservatives living in it (a certain floppy haired Vote Leave campaigner comes to mind) and stereotypically right-wing Tunbridge Wells will still contain some left wingers. Northern Ireland and Scotland have single transferable vote (STV) elections so we can see this directly in councils there - Lisburn and Castlereagh (a unionist stronghold) still has nationalist SDLP councillors represented, likewise Derry and Strabane still has unionist councillors. Perhaps unsurprisingly given that I asked this question I don't actually think any one representative can represent a whole community and I therefore think STV is the best voting system to use from the point of view of representation, or at least the least worst. Multi-member first past the post does exist but it tends to deliver blocs of representatives from the same party unless opinion is very finely balanced, and so doesn't really reflect political diversity in areas where it's used.

However, this is not to say that STV's perfect. For it to be proportional you need a certain magnitude for each seat - at least three and preferably more representatives from each seat. Six per seat seems to work well in Northern Irish elections though I would personally prefer a bit more variability in the number of candidates per seat in order to make more sensible constituencies. In terms of representation such large seats can cause some concerns - with a larger constituency you can have a more coherent area to represent than many current constituencies but at the cost of smoothing over bigger differences. A Highlands seat makes sense but obviously Inverness is not Dornoch is not Orkney is not Skye. Weird results from ill-placed boundaries can still occur but are much less likely.

These are not the same place except in the sense that they are. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

But at what point does this smoothing over become too extreme? I've personally found that in both Oxford and Cambridge that there's such a culture gap between the city and the countryside that I would consider them quite seperate communities - the difference to me seems much larger than with, say, the culture gap between Brighton and wider Sussex (where the political differences are comparably large, if not larger). Of course in an STV Oxfordshire or Cambridgeshire seat the cities have enough people that they will still elect their Labour and/or Liberal Democrat MPs, and there's nothing to stop those MPs focusing primarily on the city, but you are still aggregating arguably very different communities. Under STV it would not be possible for the cities to have their own seats without either having an excessively large House of Commons or reducing the number of MPs per seat to the point where the system loses many of its benefits.

Your mileage may vary for those exact examples, some people don't see so sharp a distinction as I do, but there certainly will be some cases where a smaller community is very distinct from the larger one it is embedded in but will not be realistically able to have seperate representation under STV. And, having mentioned my dislike for country-city mixed seats previously, these will naturally be far more common were STV enacted. You can also achieve similar results with a list system covering large constituencies rather than countries - many countries do this, including model democracy Denmark, and the UK does it in European elections. You do, however, lose preferential voting in doing this and I don't think it offers any firm benefits over STV so it's not my preference.

So what of the other system beloved of UK electoral reformers, the additional member system (AMS) or mixed member proportional (MMP)? If there is a proportional element and the rules for overhangs are robust then what size the constituencies are matter a lot less, any disproprtionality arising from drawing the constituency boundary somewhere sensible (from the point of view of representation) will be compensated for on the list vote. Obviously my personal ideal of not having just one representative per constituency cannot be attained under this system but at least constituencies that actual make sense are easier to draw if you loosen size restrictions.

However a concern I do have about MMP from a representation point of view is that you are decoupling local representation from democracy to an extent - you accept very uneven representation (for instance the CDU has a nearly clean sweep of constituency seats in Germany at the moment) but the list MPs, who represent no locality in particular (or a very wide one), make the result proportional. I think this puts representation firmly below proportionality and makes it almost an afterthought. Of course, you could also argue that the list MPs become representatives of the whole country and allow representation of another facet of the identity of the electorate and that this therefore actually strengthens representation.

If there is both a local and national aspect to identity then this begs the question - need a community to be represented even be geographical? The answer to this is simple - no.. The UK House of Commons had such seats until 1950 in the form of university constituencies, representing graduate bodies separately from the townsfolk of the city they were based in. The universities of Oxford, Cambridge, London, Wales, Queen's (Belfast) and, pre-independence, Dublin and the National University of Ireland all elected their own MPs. There were also combined seats for other English and Scottish universities. A curious sidenote is that many of these constituencies were multi-member and used STV (after its invention) - the only use of it for House of Commons seats to date.

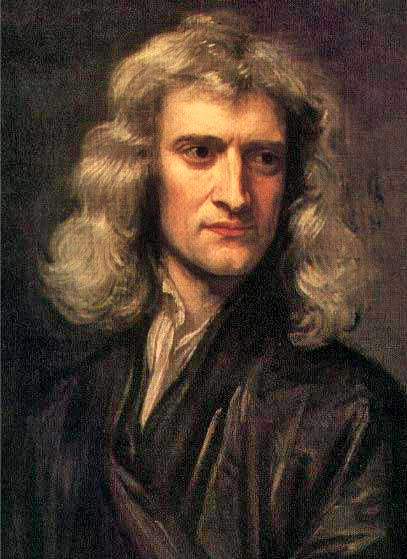

Some famous university MPs, there are many other notables who represented these seats (who are not famous): Sir Isaac Newton, former Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald, 39 Steps author John Buchan, Images from Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, this is all in the past, right? Actually, no. Although the idea of university constituencies originates in Scotland it is in Ireland where they live on: the seats for the University of Dublin and the National University of Ireland survived Irish independence and featured in both houses post-independence. They were abolished in the Dáil (lower house) after a decade or so but were retained in the Seanad (upper house), and they remain there to this day.

Furthermore, the concept of a separate MPs representing non-geographical communities exists in many current legislatures. Pakistan (which otherwise uses first-past-the-post) reserves seventy seats for women and minorities so that they may have representation, and Pakistan is certainly not a liberal country! This kind of reservation of seats for women is quite common and even for minorities is far from unique - for instance via different mechanisms New Zealand reserves seats for Maori; India reserves seats for lower castes, Adivasi (indigenous tribes) and Anglo-Indians (they do still exist!); Croatia reserves a scattering of seats for various national minorities (though some have to share - one reserved seat is shared between twelve very different nationalities!); Jordan has seats for Bedouin, Circassians and Christians, though given the king's power this may be academic; and also Iran (perhaps surprisingly) reserves seats for religious minorities. Some countries with deep internal divisions may reserve all seats for various communities - the Belgian Senate is divided by linguistic communities, Bosnia has its famous tripartite presidency (three equal presidents - one a Serb, one a Croat, one a Bosnian) and much of Lebanon's constitution revolves around inter-community and inter-religious.

Some countries have parties dedicated to representation of ethnic minorities, as opposed to nationalist/secessionist/autonomist parties á la the SNP, Plaid Cymru or Mebyon Kernow in the UK. New Zealand has the Maori and (arguably) Mana parties (both for Maori) and these kinds of parties are common in central and eastern Europe: Slovakia has two parties representing the Hungarian community (one is in government) and three for Roma, Romania has a wide array of such parties including for Hungarian, Bulgarian, German and Greek minorities and Poland has a party for the German minority.

India also has a wide variety of what are described as regionalist parties, and its third largest party (by vote share), the Bahujan Samaj Party, represents Dalits and the previously mentioned ethnic minorities in India. In a somewhat worrying outcome it failed to win any seats in the Lok Sabha on 4% of the vote in the last (first past the post) elections, but I'm sure it can take some solace in the fact that Duverger's Law means majoritarian systems inevitably slip into two-party systems making this result inevitable - which is why only 35 parties were elected in that election and a party winning less votes than it got 34 seats. More laterally you also have identity based parties in the form of pensioners' parties, with 50PLUS in The Netherlands being the most notable example.

In some cases election thresholds are waived for the ethnic minority parties (many countries have a minimum vote required to enter a legislature - often 5%) - Romania does this, as does Denmark for a party representing the German minority (though the party does not avail itself of this) and two German Länder which allow it for parties representing Danish, Frisian and Sorbian minorities.

Two unusual cases of ethnic/racial minority representation are in Hungary and the USA: Hungary has an odd system of minority lists where bodies representing national minorities can be elected to speaking (but non-voting) positions, akin to the non-voting members of the US House of Representatives (which represent territories and Washington DC). Meanwhile, some of America's (truly bizarre) congressional districts are oddly shaped not because of conscious gerrymandering but because of minority-majority districts, designing boundaries to have a local majority of a racial minority - providing racial representation. Others are just gerrymandered.

A final kind of representation commonly found is that of having overseas constituencies, where seats are reserved for nationals abroad. France, Italy and Portugal are the most famous countries having this arrangement, but there are several other countries that follow this practice. Usually these constituencies are subdivided into very large areas - for instance Italians have four overseas constituencies covering Europe, North America, South America, and the rest of the world. The USA also effectively has an overseas constituency within internal Democrat party elections, with Democrats Abroad having their own presidential primary.

I suppose the conclusion I have to draw from all of this is simply that representation can be a lot more lateral than simply grouping people by vague geographic criteria and that even that is more complicated than many often suppose. We often think of ways to improve our democracy but perhaps how to improve our representation is something that should be considered more often.