Around the World in 26 Meals: No. 13 - Burma/Myanmar

Intro

The next stop on the food tour is Myanmar, or Burma, or, in analogy to Derry/Londonderry’s moniker as “Slash City” I may just call it “Slash Country” to avoid treading on any toes.

For those that don’t know why there’s dispute on something as basic as the country’s name this ambiguity is related to the country’s unfortunate history. Said history is fascinating but even an ultra-condensed version I drafted was two long paragraphs, most of it depressing. So suffice to say the name change was instigated by a military government that overthrew the elected government in the 1960s - the very same military that overthrew the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi this year after a very brief flowering of almost-democracy.

So there’s a legitimacy issue around the name change and it has therefore had mixed adoption - the implications of the change also vary by language and ethnic group of the listener. Myanmar itself has seen quite a bit of adoption but the adjectival form (Myanma, not Myanmarese) has seen very little - Myanmar with Burmese is quite common and was what I intended to use. However, I found an interview with the author of the book I’m using and she seems to use the “Burma” forms exclusively - so I’ll follow that lead and hope no-one gets upset.

For those wanting to learn more about Burmese history I’d recommend diving in but, be warned, it’s a particularly unhappy one. Their colonial history was brutal even by the standards of colonial histories and what came before and after doesn’t seem fantastic. Granted its prior history was just absolute monarchy, most countries have at some point, but conventionally grim is still grim.

However I’m not here to linger on the sad history of Burma, be it as victim and oppressor (and, believe me, it’s been both). I’m here to advocate for its cuisine, which is something special and commonly overlooked - it’s hard to even find a Burmese restaurant even in places like London, where you can get anything. Fortunately there are multiple cookbooks covering the topic so a decent cook can have a stab at it themselves. In addition many specialist ingredients overlap with those of their neighbours’ cuisines (particularly Thailand) - making most, but certainly not all, of them not too hard to find.

As a country between India and Thailand Burma has a combination of traits from those cuisines. For instance the book I use has curry-like recipes - some of which involve typically Indian garam masalas and some of which involve typically Thai nam pla (fish sauce) and lemongrass. Though less frequent in my book there are also heavily Chinese-influenced dishes using soy sauce or Chinese preserved vegetables. Naturally, there are features of the cuisine that aren’t common in any of Burma’s neighbours’ cuisines - such as the flavour combination of pork and mango or the use of laphat - pickled tea leaves (one ingredient it actually is hard to source). It’s a wonderful combination of influences and the food I cooked for this post doesn’t reflect its full diversity.

Before I start I think it’s worth noting that Burma was and is ethnically diverse with many minority nations - this probably goes without saying for India, China or even Thailand but some may not know this about Burma. Reading between the lines of the introduction to the book I’m using the food is likely to be that of the ethnic Burmese (at least where such distinctions matter) and there’s likely to be some, possibly major, differences to what, say, the Karen people eat. Unfortunately I don’t have a book for that so I cannot elaborate!

The book

Today’s book is hsa*ba, written by Tin Cho Chaw. Unlike many cookbook authors it’s hard to find much information about her beyond what she writes herself in the book or the sole interview I could find with her. She was born in Burma, moved to Devon as a child, married a man called Christopher and had a trip seeing extended family, collecting recipes in preparation for writing this book. I don’t really know much more than that. If you’re interested in her thoughts as well as her book I’d recommend reading the interview - she has some interesting suggestions as to why Burmese food is not as well regarded as it should be for instance.

In addition there are some other recipes of hers on the hsa*ba website, as well as the odd tidbit on other topics (such as where to source laphet), though there are a lot of dead links for a site that doesn’t seem to be abandoned.

What I cooked (and adjustments)

The more substantive dishes were a slow-cooked pork belly recipe (involving soy sauce and ginger) and flat rice noodles with eggs.

As a side I made fish cakes with a sour chilli dip, as well as a danbauk salad. The latter consists of cucumber, tomato, red onion, mint, coriander and lemon - and is similar to salads elsewhere! More about it later.

With regards to adjustments - I opted for the lower end of the suggested range when coriander leaf cropped up (hypertasting) and did need to do one asafoetida for garlic substitution (partner’s intolerance) but these were quite minor changes. I do them in most posts.

However shrimp and chilli oil was a necessary ingredient for the noodles that I needed to make up myself and the recipe required dried shrimp. Which I could not find, even in the Thai grocer where I’d found them previously. So I substituted a smaller amount of shrimp paste that I had to hand instead. Annoyingly I found a source for dried shrimp a week after doing this batch of cooking while prepping for a different meal, and after I had any use for them.

Furthermore in my fish cakes recipe I ended up using red onion, the recipe simply said “onion” but I would take that to imply brown, yellow or white. The reason for this change was simple - the brown onion I was using was rotten and this wasn’t visible on the surface and I had to dispose of it. I had more brown onions but they were all accounted for in other recipes and this seemed the recipe where adding red onion would detract least.

Also the noodles I used in “flat rice noodles with eggs” weren’t flat. But they were rice noodles.

Finally, as I said earlier, I don’t think my cooking in this post really reflects the diversity of the cuisine - the Indian influence isn’t obvious for instance. Arguably some of these recipes are near identical to Chinese or Thai ones (certainly the pork belly one is) but these combinations of dishes would certainly not be normal in China or Thailand!

Cooking

The slow-cooked pork belly is best not consumed immediately after cooking, as its flavour develops over time. So work on it began a day ahead of everything else. As can be seen, the ingredients are quite simple - pork, sugar, soy (dark and light), ginger, oil and water.

Incidentally sugar in savoury food seems alarming but we’re just reaching the part of the world where that’s more and more the done thing (technically we’ve already seen it with jaggery in the India posts). Make no mistake, I’m very keen to judge cooks who overuse sugar in Western savoury food but these are just different culinary traditions in play here. In some places a sweet potato belongs in savoury food, in others in sweet food; in some places spam is a high status item, in others about as low as low gets; and in some places sugar goes in savoury food and in others it’s rarely anything but an abomination.

With my rant over, the first step was to marinade the pork and ginger in sugar and soy.

This mix was then heated to caramelise the pork and the other ingredients were added and heated at 150 degrees for a couple of hours.

The end result wasn’t the prettiest, this dish is a rare case of food that’s meant to be black! However it was tender, flavourful and delicious when served up the next day. Relatively simple and very good indeed.

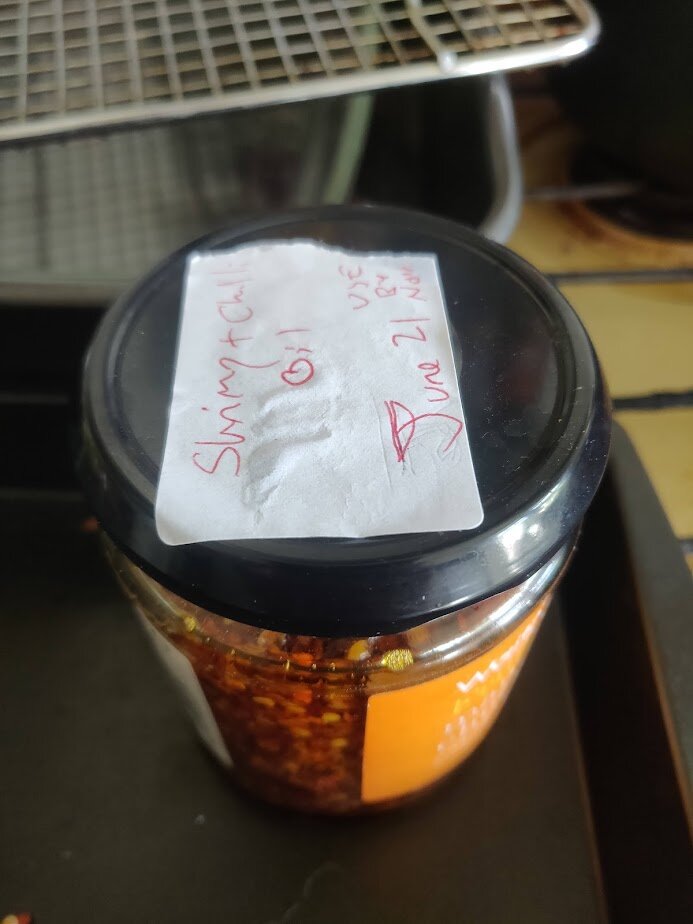

I also prepared some chilli and shrimp oil for the next day’s cooking - dried chilli flakes were heated in a copious amount of peanut/groundnut oil.

First instance of grubby hob!

As the colour of the chilli flakes began to turn I added in my shrimp paste, substituting for dried shrimps.

This was dissolved in, heated for a little while longer and then decanted into a sanitised jar - ready for use later.

Another small item needed for one of the dishes was the sour chilli dip - the basis of the sourness being lime juice. Lemon would have also been acceptable.

The chillies were chopped and added (with my garlic substitute) to the lime juice. This, essentially, was the dip - with fish sauce added to add salt and savoury flavours to taste.

Although not shown in this shot some of the coriander leaf was added to this dip before serving. Overall it was rather pleasant, if a bit insubstantial - which is to be expected given it’s mostly lime juice.

Next up is the simple danbauk salad. This is what went in:

And this is the finished article:

Overall, much as expected, a flavourful and refreshing salad. As an aside, the name danbauk salad simply means a salad to accompany danbauk - which is the Burmese name for biryani. So far as I’m aware this salad doesn’t typically have a name but is assigned this one in the book to differentiate it from various noodle salads elsewhere.

Onto the fishcakes. Like the pork or the salad there are relatively few ingredients in play here.

The fish was made into a paste in a food processor and the onion and chilli were chopped.

The fish paste was mixed in with flour and the chopped veg.

And formed into balls, ready for shallow frying.

As is quite common with this kind of recipe there were some structural issues when cooking and I think some parts of the cakes caught a bit while others were still cooking.

Nevertheless these were perfectly pleasant fish cakes and were well complemented by the sour chilli dip.

Certainly I think the pork and the (yet to be shown) noodles were more distinctive than these but the fish cakes were good on their own terms. Perhaps they were just a bit too familiar, as Thai fish cakes are a staple of restaurants and are quite similar - though the combination of the fish cakes with the sour dipping sauce is still a little apart from that.

Finally - some noodles. I could only find tinned beansprouts on this occasion but they seemed acceptable for this kind of dish.

The onion was browned and set aside, though looking at the picture some pieces could have used a bit more heat. A possibly daft thought I had regarding this is that perhaps this is some light Indian influence on a noodle dish as pre-browned onions are reasonably common in Indian food and are often credited with a recipe in their own right in Indian cookbooks.

In the same pan the beansprouts and eggs were added and stirred until the eggs were scrambled.

Then the noodles, chilli oil and fish sauce were added and stir-fried. A very satisfying noodle dish resulted, the eggs giving it a bit of protein while the oil, fish sauce and onion gave it a depth of flavour - similar but distinct from Thai noodle dishes and well worth the effort!

I doubt this combination would exactly be a usual one, given the salad is intended as a side for biryani it most certainly isn’t, but I enjoyed this meal very much.

Certainly the noodles and pork were the stars of the show but everything turned out well - the fish cakes seemed a bit too similar to Thai ones and the salad too similar to, well, salad to be distinctive but they still were good things judged on their own merits. And, had I spent a lot of time eating soy-braised pork in Chinese restaurants I may well have found that dish also a bit too familiar. It’s all good, is what I’m saying.

As a final side in this section I do avoid cooking things I’ve made before in these posts but I would like to recommend an additional recipe that I’ve made before from the book, but not for this post. This is the coconut chicken curry - it’s something both delicious and distinctively Burmese. It falls somewhere between an Indian and a Thai curry (closer to Thai) but is different enough from either to be unmistakably it’s own thing.

Dogs, again!

What I’d do differently

With this post I have a fairly boring answer to the question “what would I do differently?”. Nothing obvious to be honest. beyond the slow improvement that comes from cooking more things. And I guess actually finding dried shrimp for my making chilli oil.

Perhaps I would deep fry the fishcakes in the hope it’d make them slightly easier to handle if I was pushed for a change. But I do think most things ended up as intended and there’s not many obvious changes to make to the recipes as written.

My view on the book

As is implied I’m already familiar with this book, and am a big fan. I think it’s also implied, if not outright stated, that everything worked out pretty perfectly with the recipes. This is true but as I have used this book before I think it is worth mentioning that not every recipe works quite as smoothly as the ones in this post. Most do, but there’s a possibility that some recipes will need further adjustment should you use the book.

Having discussed the most basic functions of a cookbook - ie do the recipes work and are they good? - I’ll move onto my own mini-obsession when it comes to considering cookbooks, namely the amount of introduction content versus recipe content. In answering that question I should talk a bit about the introduction - here it is:

Apologies for the glare on these photos. With this one I attempted to reduce it but it did more to darken the image opposite the introduction than anything else! I may go back and take new photos of the book at a later date.

So, yes, it’s safe to say that this introduction doesn’t outstay its welcome. In fact, I’d say it’s actually far too little introduction. However the book has photographs and short pieces on various topics of Burmese food scattered around which effectively counter-balance the too-short introduction. These, overall, give a very good balance between introductory, explanatory and decorative content versus the actual recipes.

The photography tends to be, as is common, very stylised but good. This extends to the pictures used to illustrate the recipes themselves - most, but not all, recipes have accompanying photographs which act as useful guides for how the end product should turn out.

At this point I’m running out of much more to say in this section - which is typically an indication of something very good or very bad. Obviously, given what I’ve said, I think the book is very good - if you’re interested at all in this cuisine give it a shot.