Around the World in 26 Meals: No. 14 - China (Sichuan)

Intro

So, onto China. We all know what China is and, paradoxically, I think that there’s so much to say limits how much I will say. Typically I’d talk about influences on the cuisine and try to take us around the garden path with some tangentially related history, researched very quickly. But there’s just a bit too much to chew on this time. Suffice to say that Chinese culinary history was influenced by its neighbours and the West (chillies come to mind!) just like anywhere else. But an awful lot of food originated in China, such as the soy sauce that’s so ubiquitous in many cuisines, China’s been a huge influence on the world’s cuisine itself and a lot of its characteristic dishes and ingredients just come from itself.

However, as I can’t resist self-indulgent minor details that really don’t affect the bigger picture - China used to have dairy in its cuisine but they abandoned in at the time of the Song Dynasty (late Saxon times to high Middle Ages) - I found that a bit surprising.

Typically Chinese cookery is divided into eight great traditions - Anhui, Cantonese, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Sichuan, Shangdong and Zhejiang. Unfortunately I only have cookbooks focusing on two of these, Sichuan and Hunan, renowned for their bold flavours and heat respectively. Fortunately I was only planning on doing two posts on China so that reduces the pressure somewhat. This post is on Sichuan.

For those needing a reminder of exactly where Sichuan is, see the map below. Please note the region is larger than the province itself (Chongqing is its own province but historically was part of Sichuan). It’s far inland, is renowned for its tea culture and was historically considered a land of plenty. It’s also been renowned for its food for centuries.

Naturally, it wasn’t always part of China (as the earliest Chinese states were on the Yelllow River, north and east of Sichuan) but its incorporation occurs very early in Imperial Chinese history, details on the pre-Chinese cultures of Sichuan are a little light and it was, and still is, an important region of the country.

Finally I’d like to note that this characterisation of Chinese food into eight great traditions is an oversimplification and, to me, sounds a bit Han-centric. You will, for instance, notice the lack of reference to Uyghur, Manchu, Tibetan or Mongolian cuisine, as well as of less famous ethnic minorities in China. This is without going into the more distinctive minor regional cuisines, like those of Macau and Hong Kong, or the food of Taiwan - the other China. There’s a whole world of different cuisines hidden within big countries like China, far more than can even be skimmed in this kind of blog and, quite possibly, more than can be adequately explored in English-language cookbooks.

The book

For this post on Sichuan cookery I’ve decided to use the book Sichuan Cookery by Fuschia Dunlop in order to allow me to do some Sichuan cookery. See what I did there? Maybe I’ll go and listen to a song about a black sabbath while I cook - maybe Black Sabbath’s Black Sabbath on their album Black Sabbath. (You can also make this lame joke with the band Electric Wizard.)

Jokes aside I do actually prefer this to the US Title, Land of Plenty. There is a degree to which my taste in cookbooks and their titles is a bit utilitarian - something that may have come across in these posts. Obviously in the long run having dozens of cookbooks with very practical names does run into the classical music problem, where titles become difficult to distinguish, but until that happens I’m in favour of Ronseal cookbook titles. As the world isn’t exactly awash with English-language books on Chinese regional cuisine it’s a problem that’s very far away in any case, at least for this kind of book.

Now, some astute people may note that Fuschia Dunlop is not a very Chinese name and, indeed, it’s not. She is, in fact, British. However she spent a long time living in China, has won multiple awards for her work and acts as a consultant to high-end Sichuan restaurants. Although typically it’s good that an author writing a book on a particular cuisine is from the relevant country I think she’s more than proved herself knowledgeable on the topic!

What I cooked (and adjustments)

The main course I picked was a somewhat dramatic dish - pork in lychee sauce with crispy rice (guo ba rou pian/ping di yi sheng lei) - where a sauce is poured over crispy rice and it makes popping noises. Somewhat less impressively the lychee in the title is not meant to be taken literally, it’s just an analogy and the sauce is mostly made from fairly standard ingredients for Chinese cooking. No pointy eyeball fruit for you.

I expected there’d be some finesse in getting that dish to pan out and I was aware that I might not pull it off. So a simpler main, shredded beef with sweet peppers (tian jiao niu rou si) was also planned - to go alongside the pork if all went well, to replace it if things went very badly.

Apparently I never learn how much is too much so I selected a third main course was selected - dan dan noodles, apparently famous street food in Sichuan. Beyond noodles the main ingredients are pork mince, spring onion and either ya cai (preserved mustard greens) or Tianjin preserved vegetable (a type of preserved cabbage from northern China). Neither option for the last ingredient is easy to source so which one I used was determined by what one I found first - in this case it was Tianjin preserved vegetable, probably helped by the distinctive clay pots it’s sold in.

Also I wanted to do some buns. So I made steamed buns with spicy beansprout stuffing (dou ya bao zi). Despite the name they aren’t vegetarian and also contain pork mince - despite my joking in the last paragraph the noodles were actually chosen so I could use the excess pork mince from these buns, my nearest butcher doesn’t really do pork mince without advance warning and the shops only sell it in 500g packets.

Finally there was one notable omission from all of these recipes. Fresh vegetables. Strictly speaking there was spring onion in the noodles, that and some leafy veg in the pork dish and beansprouts in the buns but I wanted something that would taste a bit fresh and cut through some of the stodge of this meal. So I also made fine green beans in a ginger sauce (jiang zhi jiang dou).

In the end there wasn’t too much in the way of substitution and adjustment needed - I tend to stick a bit more to the letter of the recipe with Chinese food, as the principles behind a lot of the flavouring seems unintuitive to me, only one recipe used garlic (so no need to sub) and no recipes used coriander (so no need to reduce). The only substitution ended up being using pickled chillies from the Mediterranean in lieu of Sichaunese or Thai pickled chillies in the pork in lychee sauce. Given that sourcing ingredients for this post was far more difficult than usual I’m quite proud of that.

Granted I did also use my homemade chilli and shrimp oil instead of plain chilli oil but I’m not too sure substituting chilli oil for chilli oil really counts!

Cooking

Once again I left quite a gap between cooking and writing up, so the order of the dishes will be quite arbitrary. However, I’ll begin with the dish I started first and finished last - the steamed buns.

As the name “bun” would suggest the process for making these is actually quite comparable to making bread. With one major difference that we’ll see at the end. So I started off with all the usual ingredients for making bread - flour, sugar, water, yeast, Kellogg’s Crunchy Nut.

I’m sure most of you have seen a dough being made, anyone who’s read these posts chronologically certainly has, so I didn’t take any pictures of the process. Suffice to say this dough looked very much like you’d expect.

The next step was to prepare the filling for the buns. Next to the rising dough we can see peanut oil for frying and the filling components - pork mince, Shaoxing rice wine (an essential ingredient for Chinese food that’s mercifully easy to find), chilli soya paste (more on that in a tick), salt, light and dark soy sauces, black pepper, beansprouts and Alpen.

A fairly time consuming step followed - the filling for the buns involves fresh, trimmed beansprouts. So I got to chopping. It all took a while but, as it turns out, trimmed beansprouts actually look quite nice.

The pork was browned before chilli soya paste was added, followed by the trimmed beansprouts.

This is where I talk at you about chilli soya paste for quite while. There are different varieties of this ingredient, the Korean version (gochujang) is the easiest to find in my experience with the Sichuan version (often called pixian, after the most famous town producing it) being much more elusive.

Which isn’t to say it’s always been easy to source. When I first started cooking with chilli soya paste gochujang was the only one I could find (and that with difficulty). And I knew it primarily as an ingredient for a dipping sauce served with the Korean variant of sushi - as an undergrad me and some friends, one of whom was Korean, had a go at making it.

Gochujang has since, deservedly, taken off - I’ve seen it in Sainsbury’s Local in my city and have noticed English translations appearing on the box itself, next to the hangul and no longer relegated to the familiar white translation sticker whacked on Asian products by the importer. My takeaway burger the night before starting writing this post came with gochujang chicken nuggets - give it a couple of years and the ingredient may be so mainstream that italicising it will seem old-fashioned and weird.

Pixian hasn’t taken off in quite the same way and was initially difficult to find in a way that the book absolutely did not prepare me for. The introduction made it seem like an ingredient that’s not too difficult to locate but, in practice, I spent quite a while hunting and when I did find it the discussions I had at the shop implied they’d only recently found a supplier.

As with many unfamiliar ingredients, it can be hard to recognise it even if you’re staring right at it (unless you read Chinese) - once you’ve found it once and recognise the packaging it’s actually a lot easier. Maybe it has only recently been sourced by the oriental supermarkets but I’ve seen it crop up in more than one now I know what to look for.

And what is the difference, beyond where they come from? Simply put - gochujang is sweet, pixian is earthy. The ingredients absolutely can be substituted for each other if desired (I’ve been cooking a noodle dish called ants climbing a tree using gochujang rather than pixian for over a decade) but you would notice the difference in a taste test. If you subbed gochujang for pixian I’d expect it would be comparable to if you subbed Scotch bonnet chillies for ancho chillies, perhaps slightly less noticeable as (of course) one of those chillies is dried and one is fresh, whereas both pastes are pastes.

Tangent over. Back to cooking.

Now we have a bowl of bun filling - in real life there was a long gap before I made the buns themselves. In this blog there won’t be, because that would be boring.

“By the golden light of the setting sun

I made a big sosig of dough

Then chopped it in bits

And squished them bits until they got all flattened”

A bit roughly, a bit unevenly, I filled the parcels and twisted the dough so there was a little spout at the top of each bun. I’m dyspraxic so there was only so neat they would ever realistically be but I think they panned out alright considering.

And, in an upgrade from the last dumplings I did (the momos), I had acquired a dedicated steamer as an early birthday present. And it was an absolute lifesaver - the buns were laid on baking paper, the steamer filled with water and I could just relax and let the machine do its job. Obviously this is where these buns are treated very much less like bread.

And they were spectacular. Utterly delicious with a complex flavour, structurally they were sound and they were probably the best buns/dumplings I’ve done. Aesthetically they were a little rough but taste-wise I’d happily pay for these in a restaurant.

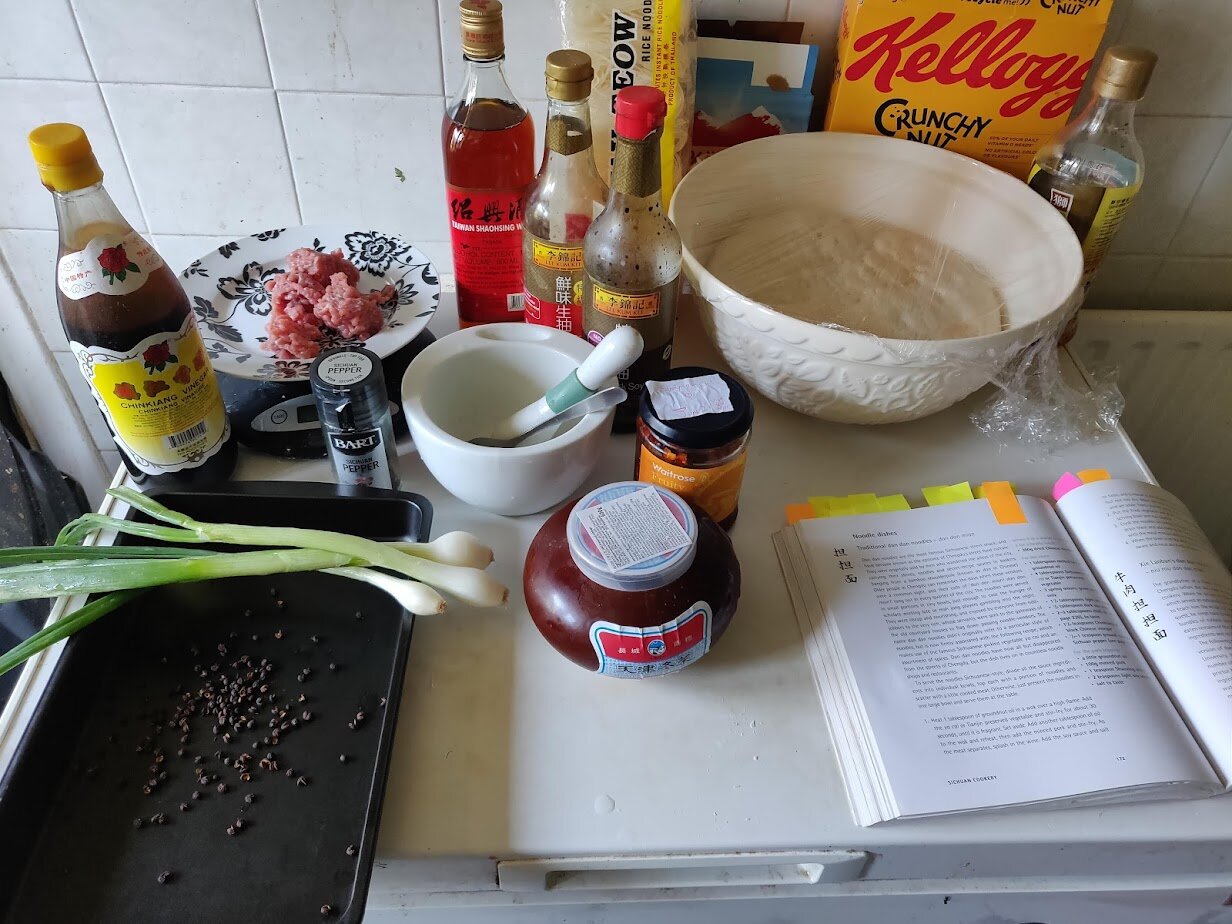

Now to use the rest of that pork mince. Dan dan noodles. In this shot I prepared peanut oil, both types of soy sauce, Shaoxing again, Chiankiang vinegar (another common ingredient), sichuan pepper (you know this one!), the noodles (behind the soy), my chilli and shrimp oil from the last post, spring onion and some preserved vegetable.

Coincidentally Shaoxing and Chiankiang are also both from the same province of China - Jiangsu (just north of Shanghai). That doesn’t really relate to the cooking process but I’ve used these ingredients for a long time and never knew that.

Just toasting some sichuan pepper, don’t mind me. (I’d wrongly thought you’d toast them in the oven in the previous photo.)

And, apparently I forgot to take pictures. Suffice to say the process involved frying the Tianjin preserved vegetable separately, then frying the pork, adding the wine, cooking until crispy and then mixing in all the ingredients.

Appropriately as my views on this were mixed. I liked it fundamentally, it was a nicely balanced noodle dish at its core, but there were some significant issues as well.

Some aspects where the dish fell short were due to my cooking - the noodles stuck together too much but perhaps I could have done something to minimise that. But the biggest problem, quite simply, was the Tianjin preserved vegetable.

When a mouthful of the dish contains any of this the preserved vegetable absolutely dominates with its saltiness - either it needed more rinsing (quite likely) or I should have held out and tried to find ya cai, the other acceptable vegetable for dan dan noodles. A mouthful of the noodles without any preserved vegetable, however, was very pleasant.

For something fresher we now move onto the fine beans, photographed evidently when everything was go. The Chinkiang vinegar, chicken stock, ginger and yard long beans were the only ingredients photographed (sesame oil was also used).

I made the simple sauce (literally cut up ginger combined with the liquid ingredients, with the sesame oil added last) and chopped up the beans into manageable lengths.

I’d then briefly boiled the beans and, simple as that, I combined everything and it was done.

These beans were perfectly pleasant but surprisingly bland - the sauce gave such a gentle flavour that there wasn’t too much to distinguish this dish from plain beans. And, as it turns out, yard long beans don’t taste very different to French beans so this all felt very familiar. However, in a meal so heavy with salt and oil it was just the tonic needed, so at least it worked contextually.

Dirty hob again!

Onto the shredded beef. Once again I prepped ingredients for a photo - stock, potato flour, Shaoxing wine, light soy, salt, sweet bean paste (Korean) as well as, obviously, beef and peppers.

Incidentally potato flour in this context is also known as potato starch or farina and is often a pain to track down. In some other contexts potato flour can refer to something subtly different and in US English farina refers to a different (wheat-based) grain product. But, if you want to cook from this book take the three terms as being interchangeable.

However I’d expect cornflour would be suitable to use in lieu of potato flour, as potato flour is itself a substitute for a kind of pea flour that’s rarely sold outside China.

Some chopping and mixing. I actually can’t recall what’s in the glass, as there is a sauce and a marinade (for the beef) in this recipe with fairly similar ingredients.

I fried the beef on a high heat, then added sweet bean paste, peppers and sauce in that order.

And the end result is a bit more oily than I’d like but broadly it turned out well. The beef was flavourful and the flavours of the sauce, peppers and marinade complemented it well. Perhaps not the most adventurous dish in this post but I think it panned out well!

Finally we have the pork in the lychee sauce. Once again I’d arranged the ingredients for a shot - pork, Shaoxing, light soy, salt, dried mushrooms (soaking), ginger, bamboo shoots, pickled chillies, choy sam (it’s the vegetable that looks a bit like bok choi), spring onion (hiding out near it), asafoetida (as garlic substitute), stock, sugar and Chinkiang vinegar. There’s also sesame oil but I forgot to get those in shot.

The most obvious missing ingredient from this is the rice - after all, this is pork with crispy rice! Some pre-boiled rice was prepped to bake in the oven at a quite low heat for a long time, shown below (and, after cooking, in the background of a lot of other shots!).

I marinaded the pork as per the recipe. I’m keen to not make these recipes reproducible from these posts but the marinade was made of soy, Shaxoing and salt. Amounts unspecified!

Also in shot were the horse-tail chopped chillies and spring onion (combined with asafeotida as they are all to be cooked at the same time); a plate containing the drained mushrooms, choy sam and bamboo shoots; and the beginnings of the sauce with most liquid ingredients, including the mushroom water, combined with the sugar and some salt - potato flour, vinegar and sesame oil were added later.

Then I fried the pork, adding extra ingredients step-wise; tended to the sauce and deep fried the rice in a pan.

With the sauce ready and the crispy rice deep fried it was time to combine them and make everything POP!

Dear reader, the rice did not pop. In reality the crispy rice just introduced some unpleasant textures to the dish. This may be because, running out of vessels, I combined the sauce with the rest of the food too early instead of combining hot sauce with hot rice as the recipe suggested.

However, the rest of it was genuinely delicious, with complex, delicately balanced flavours complementing each other (though, again, it ended up a smidge too oily, as can be seen in the photo). Truth be told, I don’t know how best to judge a dish that’s half an unambiguous failure and half a great success.

Here it all is. Perhaps it was a bit too shiny to be pretty and many of the dishes had some flaws but overall I think this was still a good meal. The buns and the beef were excellent and, truth be told, I expect everything but the beans had the potential to be, had I executed the recipes better.

No dog tray today.

What I’d do differently

Firstly, I’d not change anything about the buns. I loved them. Everything else, however, needed a bit of adjustment - which is surprising as I do already use this book quite frequently and can usually follow it faithfully and get good results.

With that said, the biggest changes were needed in the pork and crispy rice dish and I think my combining the sauce and meat too early, contrary to the recipe, may have been detrimental to getting a good result.

Nevertheless there was more wrong with how that dish turned out than just that one factor - perhaps I needed to keep the sauce and rice hotter? At the time I made this food there were problems with the extractor fan (and lights!) in the kitchen so I’d have been reticent to use a proper deep fat fryer for the rice. I expect that would have better results than attempting deep frying in a shallow pan so that seems another obvious adjustment.

I’d probably also try to slightly reduce the oil used for shallow frying in this recipe, as a bit too much got into the final sauce. I’d also do this for the beef.

With the beans, honestly, I’d just not bother with yard long beans. French beans would taste very similar and be a lot cheaper. As much as I was underwhelmed by the bean dish I do think it panned out as intended so I see no need for any further changes here.

Which leaves only the noodles - where there were two obvious problems. Firstly the noodles themselves sticking - perhaps leaving them soaking in water after cooking or coating them in oil would help? This sticking issue doesn’t occur with every rice noodle dish I prepare so it may also be an issue of letting it sit for too long between cooking and mixing.

The second issue is Tianjin preserved vegetable. Maybe it needs to be rinsed a lot more. Maybe it just needs replaced by other ingredients. Something to be experimented with I suppose.

My view on the book

As happens often in these posts I have used the book previously and highly rate it, so the overall impression will be positive, despite having had some difficulties with this post’s dishes. I’m not sure how much choice there is if you want a specifically Sichuan cookbook so even if I hated it there wouldn’t be many other options!

Now, to get my usual obsession out of the way let’s talk about how long the introduction is versus the rest of the book. The introduction is 75 pages long, with the rest of the book tallying at 275 pages.

This is a very long introduction but given the context of this book I’m actually very forgiving of that. In my experience sourcing specialist ingredients for Chinese food is a fair bit harder than for any other well-known cuisine (and many obscure ones) and, honestly, a long introduction talking about authentic ingredients and what you can substitute for them if need be is very welcome. Particularly for fresh vegetables which can be a nightmare to source. For the super keen there’s also a lot on Sichuanese cooking and cutting styles, again, quite practical.

Certainly the usual introduction-type content about what Sichuan is, what its history is like and so on is also present but don’t make the mistake of thinking the introduction is a massive tangent - if anything it’s the most important introduction section I’ve seen in a cookbook.

I would, however, criticise two things - some sections in the introduction drastically misrepresent how easy it is to find certain ingredients (for instance, Chinese chilli soya paste or rock sugar). On a similar note sometimes too much space is given to describing a familiar ingredient over an unfamiliar one - as an example peanuts get a lengthy paragraph whereas overleaf Tianjin preserved vegetable appears only as a footnote to ya cai (preserved mustard greens), and with information so scant that it doesn’t tell the reader to rinse it before use or what vegetable it is that is preserved near Tianjin in the first place.

The body text also continues the trend of providing contextual information about the cuisine. Not all of the 275 pages of body text are dedicated to recipes - there are appendices on more general points of cooking (for instance descriptions of how Sichuanese cooks describe flavours and techniques) as well as a very useful index and, of course, flavour text. Broadly these text sections outside recipes are quite few and far between but some of them can be rather lengthy - four pages are dedicated to discussion of hot pot, for instance. Overall they do add something to the book and these sections aren’t so voluminous to give the impression that they’re padding or taking space away from the actual recipes.

As can be seen in the photo below the recipes are packed in very tightly, but often have quite lengthy introduction sections which are usually quite tightly related to the recipe at hand - though some diversions are allowed such as an amusing anecdote about a completely ordinary recipe found in a 1980s cookbook that was marked as classified state information for no obvious reason. As if state security would be in jeopardy should the West how they cook liver in Sichuan.

While discussing the recipes (which I find usually work well) there are two notable quirks to be addressed.

Firstly, the philosophy of the book leans heavily towards authenticity of ingredients over accessibility. This is not without exception, I briefly mentioned how potato flour is a substitution made by the author and there are others (Chinkiang vinegar is a substitution for Baoning vinegar throughout the book), but on the whole checking the introduction when faced with a difficult to source ingredient is wise. Broadly this is the approach I prefer but I don’t think it’s obvious reading the recipes in isolation how useful referring back to the introduction can be.

Secondly, as can be seen the recipes (although made to look attractive with the calligraphy) lack photographs for illustration, so if you don’t know what the dish looks like you’re on your own. Or with Google, at least. This is perhaps a necessary trade-off given the density of the book and certainly preferable to dropping recipes but is, in itself, a bad thing.

However I did actually tell a small fib there. Despite what I just said there are photos in the book, and they’re rather pretty, they’re just not very useful to actually help a reader know how the recipe should turn out. These photos are clearly on a different paper stock to the rest of the book (which is monochrome) and are clustered together, excluded from the page count. There aren’t very many of them, not all of them are photos of completed recipes and of those that are not all have page references.

Despite my criticism I do think this is actually an essential book when it comes to this cuisine and that it takes care to explain what it can for cooks unfamiliar with this kind of cookery. However it does have an air of being all business, which may seem a bit intimidating for some. As for myself, I think of that as a positive and a way of incorporating more recipes and more detail into a book.

So I think it’s pretty great. This was Fuschia Dunlop’s first cookbook and we’ll be doing another one of hers next time. A different region of China (Hunan) and, to some extent, a different style of book.